[The Montana Professor 16.1, Fall 2005 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

William W. Locke

Earth Sciences

MSU-Bozeman

wlocke@montana.edu

About 15 years ago I began to notice that without incentives such as pop quizzes attendance in my large introductory classes was dropping to 60%, 50%, and even 40% of enrolled students. I wondered if I was losing my touch, and if I should try to compete with entertainment through skits ("Thar's gold in them thar hills!") or period costumes. Other faculty, however, report similar attendance declines, and I began to wonder whether we weren't facing students unlike those for whom we had prepared to teach. The behavior of many of my students reminded me of my time in high school, rather than my own undergraduate days.

For many of us, the quintessential separation of high school and college was graphically illustrated in George Lucas's (1973) classic film American Graffiti. The clean-cut, chino-and-chenille-clad Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) and Laurie Henderson (Cindy Williams) and Steve Bolander (Ron Howard) are in stark contrast to the jeans and tee-shirt, cigarettes-tucked-in-the-sleeve, no-future-life of hotrodders John Milner (Paul Le Mat) and Bob Falfa (Harrison Ford). The first three are headed off to college and success in the broader world while the latter two are trapped in Nowheresville. Does the American Graffiti picture of the college bound hold in the students in our classes today?

Much of what we do in higher education is conditioned by the way higher education is viewed by our parents, ourselves, and our children and grandchildren (whom we are now teaching). Here, I look at the demographics of higher education as the dominant driving force behind some of the symptoms we see as a miasma affecting higher education.

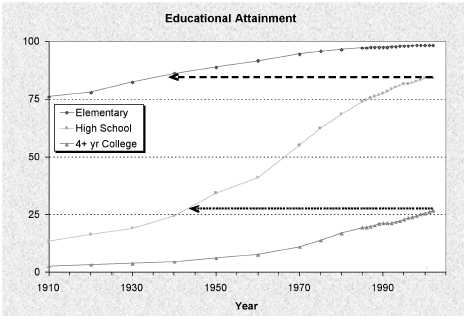

Statistics are available for education in the United States since the mid-1800s--see <http://nces.ed.gov/>. I have crunched a few of them to try to put a face on the transition in public perception of education. For example, about a century ago, only about three-quarters of Americans over 25 years of age had achieved an elementary-school education, less than 15% had completed high school, and a mere 2.5% had completed 4 or more years of college (Figure 1).

Figure 1. American educational attainment by year

College was viewed as diversion for the idle rich, as well as a challenge for the few who might aspire to a professional career. By the beginning of World War II, elementary education was beginning to saturate, with nearly 90% of white Americans completing six years (but only 60% of black Americans). The climb to the current value of nearly 99% of all Americans is a measure of the assimilation of all cultures into our educational melting pot. But, at least in the last century, universal elementary education has largely been viewed as a common birthright. In contrast, high school completion has evolved from an exception in the early years of the 20th century to an expectation at present. About 88% of white, 79% of black and 57% of Hispanic Americans were earning at least a high school diploma by the year 2000; about the same proportion who had earned such a diploma at the beginning of the century were failing to reach that level by century's end.

It was once acceptable and indeed laudable to take on a family and a farm with no formal schooling beyond grade 6; now it would be viewed as irresponsible. Over that same century the proportion of Americans earning college degrees or more has increased by a factor of ten, with more than 1/4 of Americans (nearly 30% of white Americans) now holding at least a four-year college degree. Although this trend began with the numbers taking advantage of the post-WWII GI Bill and the subsequent Baby Boom, it has continued as a pervasive social trend.

To look at the same numbers a different way, the same proportion of Americans now complete high school as completed grade school at the outbreak of World War II (dashed arrow in Figure 1) and the same proportion of Americans complete college now as completed high school at the end of that war (dotted arrow in Figure 1). In terms of its service to society, college is now understood to fulfill the same purpose of providing a minimum life foundation and skill set as high school did 60 years (two generations) ago. Thus it could seem that our parents' perception of American Graffiti matches our children's perception, except that our children would see Curt, Laurie and Steve as going on to graduate school while John and Bob "only" graduate from college.

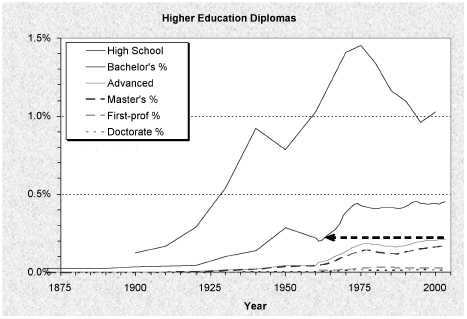

If anything, the educational pace has quickened (Figure 2). If we look only at the proportion of Americans earning a specific degree level in a given year, the rate of college degrees awarded in 1970 matched that for high school diplomas in 1925, and the current rate of earned advanced degrees (Master's, first-professional, and Doctorate) matches that of earned baccalaureates as recently as 1963 (dashed arrow on Figure 2)! The societal perception of a bachelor's degree when I entered high school matches the current perception of a graduate degree for today's elementary school graduates.

Figure 2. Proportion of Americans earning given diploma each year

What is the source of the new college student? If the "college boy" of the 1800s was drawn only from the financial and intellectual elite, then there were many untapped sources from which to draw today's college student. Women have been added to the mix at comparable proportions to men: there should be no downside to that increase in clientele. The same can be said for other underrepresented groups. However, there is no question that some of the new high school graduates are those who would have dropped out or flunked out when high school was optional; they now are driven to attend college whether they are qualified and motivated or not.

What does this change in demographics mean to us in the Montana University System? I see lack of motivation as the fundamental difference between today's entering students and those "when we were in college." Just as we remember, when we were in high school, students trapped in the system waiting for a chance to escape, so are many of today's college students waiting for that chance. Although I have flunked only perhaps a dozen students (who tried their best, but failed) in over a quarter-century, I commonly flunk a dozen or more each semester who choose to fail (I term it "academic suicide"). If the syllabus specifies a limit ("missing four or more labs will automatically constitute failure in the course"), they will push that limit until failure is inevitable, then seek to point the blame elsewhere. Their most apparent problem is not the intellectual capacity to complete college work successfully--it is the motivation.

The late Yale historian of science Derek J. de Solla Price (1963, 1986) concluded from studies of citation practices that the quantity of scientific information grows at about 7% per year, thus doubling in little more than a decade./1/ Every 50 years, knowledge increases by an order of magnitude. Thus, there is about 10,000 times as much available knowledge now as there was in 1800, when four-year colleges expanded explosively across the American landscape. A four-year college program has remained the rule, but the amount of available knowledge has increased many times over. Even allowing for replacement of outmoded knowledge with new, the amount that is available to be learned in college now far exceeds what was available to be learned only a generation ago. Every high school and college graduate today knows less as a proportion of available knowledge than did his or her predecessors in 1950, 1900, 1850, or 1800. It follows that in order to reach a desired level of knowledge, today's students have to stay in school longer.

This puts us as faculty members in an undesirable position. What is the goal of our profession? Is our job primarily to keep students in school to retain their social position? Is it to recast our curricula to make them more palatable to a less motivated and less capable clientele? Is it to serve as gatekeepers, restricting academic advancement to only a favored percentage? Or is it to intensify our teaching and learning activities to try to keep students comparably competent to recent and not-so-recent graduates? I would hope that no reader thinks he or she has the unique correct answer to this question--society, the Regents, and your peers can each invalidate your personal decision by their decisions around you.

As long as college is seen as the inevitable next step after high school, rather than as one of several attractive options, it will continue to be a place where young adults grow socially but fail academically, (even though they may, in fact, pass their courses and get a degree). I shudder to think how those people will treat us when, as voters, they have a say in how public universities are run and funded. As an alternative, I would encourage us to think about breaking the education habit. Universal public service (although widely condemned for other reasons) might be one way to afford high school graduates with the opportunity to think about their future aims and goals rather than simply sleepwalk towards the future with their friends. Until the time when students make a conscious choice to commit to their education, as opposed simply to passively experiencing it, accommodating a large, unmotivated clientele with a high turnover is our fate.

Notes

[The Montana Professor 16.1, Fall 2005 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]