[The Montana Professor 19.1, Fall 2008 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Brady Harrison

English

UM-Missoula

barry.harrison@mso.umt.edu

I first encountered the work of Leslie Fiedler when I was an undergraduate at the University of Alberta, some twenty-five years ago. I was taking a course on "The Nineteenth Century American Novel," and the professor had assigned the Norton Critical Edition of Mark Twain's classic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In addition to the primary text, the edition included early reviews, Twain's letters to friends about the novel, a section dedicated to a not-so perplexing textual problem—"The Raftmen's Passage: Should It Remain?"—and sources that Twain may have drawn on for characters and incidents. More, in a treasure trove for a budding English major, the edition also offered a number of exemplary scholarly articles on the novel, including work by such luminaries in American literary and cultural studies as Bernard DeVoto, Lionel Trilling, Henry Nash Smith, Judith Fetterley, and others.

The critical appendix also boasted one superb provocation: Leslie Fiedler's "Come Back to the Raft Ag'in, Huck Honey!" What to make, he asks, about the pairing, in canonical, nineteenth century American novels, of a white protagonist with a man of color in settings largely, if not entirely, devoid of women? Wow: what indeed? So this, I remember thinking, was criticism: sly, comic by turns, yet deadly serious and—if I was a judge of anything in those days—dedicated both to saying what needs to be said and to saying what needs to be said in the service of human dignity. All of this no doubt took many years to sink in, but when I had the good fortune to be hired at the University of Montana, I was awed to learn that Fiedler had written this essay—and other landmark works—while on faculty at what in those days was Montana State University. I was in the same department that had had the great good sense to hire perhaps the greatest wild man of American letters. Although I am certainly no Leslie Fiedler, he remains one of my heroes and his work stands out as some of the smartest, most provocative in the study of American literature and culture. A pioneer in what would become such fields as gender studies, queer theory, Western studies, postmodern literary studies, and more, Fiedler was ahead of his time and must be numbered among the greatest American scholars of the twentieth century.

Before we take up Fiedler's work as a teacher and as a writer-scholar, we can abstract a brief biography from his Curriculum Vita [sic] (still posted on-line for the curious to consult). Fiedler was born in Newark, New Jersey, on March 8, 1917, and attended public schools in Newark. He earned a B.A. from New York University in 1938, an M.A. from the University of Wisconsin in 1939, and a Ph.D. from the same institution in 1941; he began his academic career as an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin (1940-41). He was then hired in 1941 by Montana State University and remained on faculty until 1963, serving as chair of the department from 1954-56. During the war years, he temporarily left Montana and studied at the Japanese Language School at the University of Colorado (1943-44) and served as a Japanese interpreter with the United States Navy from 1943-45, taking up postings in Hawaii, Guam, Iwo Jima, China, and Okinawa. Before returning to Missoula, he undertook post-doctoral studies at Harvard University (1946-47).

In 1964, after more than twenty years' service at Montana State, Fielder was lured away from Missoula by the State University of New York at Buffalo. In 1973, in recognition of his achievements in American letters, he was awarded the Samuel L. Clemens Chair in English, and he continued to teach and mentor at SUNY-Buffalo until his death on January 29, 2003. Along the way, and as his CV recounts, he took up visiting positions at "the Universities of Bologna, Rome, Paris, Venice, Athens, Sussex, and Princeton," and "lectured widely at universities and colleges throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, England, Italy, Tunisia, Ireland, France, Germany, Japan, India, Greece, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Brazil, the Netherlands, Denmark, Spain, Israel, Venezuela, and Korea." More, he served as an advisory editor for a number of presses and academic journals, and was awarded, among other honors, two Fulbright Fellowships, a Rockefeller Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1994, he was awarded the Hubbell Medal for Lifetime Contribution to the Study of American Literature by the Modern Language Association. To say the least, Fiedler had a long and distinguished career.

In his sixty years—give or take—in the profession, Fiedler was an extremely productive scholar and creative writer. Even as he remains best remembered for his critical work, he thought of himself as a scholar-essayist-writer-poet all-in-one, and he moved easily between what others, he argues, sometimes wrongly think of as different genres of writing. As he remarks in the Preface to A New Fiedler Reader (1999), "I have never managed to remember—indeed, I never quite understood—the differences between making stories and criticizing them, asking my readers to respond to both with the same act of poetic faith" (xvi). A ferocious, seemingly tireless writer, he wrote, co-wrote, or edited over twenty books and countless articles, essays, stories, and poems. In 1955, when he was nearly forty, he published his first book, An End to Innocence: Essays on Culture and Politics, and in 1996, his last book (excluding reprints or updated editions of many of his works), Tyranny of the Normal. Although we cannot here list even half his titles, a brief sample should suffice to demonstrate the range of his talents and interests. In 1958, The Art of the Essay appeared (revised 1969), and in 1962, his first collection of short fiction, Pull Down Vanity and Other Stories. In 1969, he published Nude Croquet and Other Stories; in 1972, his landmark study, The Stranger in Shakespeare; in 1978, Freaks: Myths and Images of the Secret Self; in 1982, What Was Literature?; and in 1991, Fiedler on the Roof: Essays on Literature and Jewish Identity. More, his poetry appeared in such acclaimed journals as Partisan Review and Poetry, and his fiction in Esquire, The Kenyon Review, and other literary magazines. And if all this were not enough, he also published in Playboy; as he laments, many of his works "originally appeared in contexts which falsified them"..."In the glossier magazines, they appeared in the midst of nude fold-outs, panel cartoons, and ads for beer, cigarettes, men's clothing, women's underwear: alien landscapes irrelevant to the ones in which they had been imagined or which they tried to evoke—libraries, classrooms, and the vanished streets of Newark, Missoula, Rome, or Buffalo" (Preface xv). Oh, well—he suffered for his art, and he seems, if we can judge by the sheer number and diversity of his publications and presentations, always to have been burning with great energy and ideas. Like Emerson, he possessed a mind on fire (and, like Emerson, he certainly did not mind offending people).

As a teacher, Fiedler might well serve—at least at first glance—as a model for the eccentric yet brilliant professor. He liked to smoke cigars in his office—ah, the good old days—and smoked so incessantly that his cardigan front was most often covered in ash and burn holes; he was so little concerned with matters of fashion that he appeared to wear the same clothes everyday (whereas, it seems, he satisfied his clothing needs by purchasing a number of each wardrobe item); he never managed to order books for his classes but gave students extensive reading lists and left it to them to track down the assigned texts (not necessarily an easy task in the days before internet booksellers, especially since Fiedler's classes were most often over-enrolled); in lieu of detailed lecture notes, he would usually bring a matchbook-sized scrap of paper with some scribbles on it to his three hour graduate seminars, and yet stayed on track, both in class and over the course of a semester; he had wild hair. Best of all, he seemed to have read everything, from the Romans to the Victorians to contemporary writers of the American West, and he enjoyed and admired the lowbrow as much or more than the highbrow, and sought (decades before the rise of Cultural Studies in American universities) to get his students to do the same. From my conversations with people who knew Fiedler well, I have this image of him as someone who shows up for class looking like he's just been hit several times by lightning—his hair stands on end and he's still smoking from various strikes—and then proceeds to dazzle his students (and the frequent visitors from the community who were always welcome to attend his courses) with his wit, erudition, and passion.

While it may be fun to think of Fiedler as a nutty professor, he certainly wasn't a cartoon figure, but rather an exceptionally generous, encouraging, and open-minded teacher and mentor as Casey Charles and Nancy Cook, two of my colleagues who knew him well from their days as graduate students at SUNY-Buffalo, attest. In conversation, they both noted not only l'eau du cigare that followed Fiedler around, but the fact that he held far more office hours a week than any of his colleagues; open not only to students but to anyone who wanted to stop by to discuss ideas about literature and culture. More, Fiedler was incredibly patient and kind toward his students, encouraging them to make what connections they could: who knows where an idea or leap may lead? If he seems to have been a little less generous toward his colleagues (he practiced some of his wildman, stir-things-up tactics in the hallways, department meetings, and conferences), he pushed his students, according to Cook, "to think harder and to make (unexpected, wide-ranging) connections"; and, because he had, he "made me read everything." As evidence of his dedication and generosity toward his students, he served on committees and mentored students on topics as diverse as Renaissance literature, Twain, the History of the Book, and Stephen King. As a teacher, he was by all accounts as great a listener and guide as he was a lecturer and public speaker.

Charles, the current chair of UM's department of English—and therefore following nicely in Fiedler's footsteps—celebrates these qualities of generosity, capaciousness of mind, and openness to others and new ideas in his recollections (which I quote here at length) of Fielder in the classroom:

I took a class with Leslie Fiedler on Walt Whitman at SUNY-Buffalo as a graduate student in the late 1980s. As part of his commitment personally and politically to populism, Leslie became famous for holding office hours from 9 to 12 every day and encouraging any- and everyone to drop by and talk about anything, as he puffed on his cigars and listened to students spell out their ideas. I overcame my trepidation on a few occasions to come in and talk about Shakespeare and homoeroticism, and to my surprise found him unassuming and supportive. I think he was pleased to hear about scholars who were expanding the notions of male relations he began to develop in The Stranger in Shakespeare and other works.

In the graduate seminar on Whitman, the same populist ethos was at work. I understood why he was reputed to have stood on a soapbox in Brooklyn at one point in his career; Fiedler could not have been over 5 foot 6 inches, diminutive in stature in spite of his commanding visage, beard and straggly hair often pushed back with both hands. He would come to class with a note card that he held in the palm of his hand, and for the next half hour he walked around the seminar room, discussing his approach to Whitman's work, which he thought best understood in contrast to the popular poetry of the mid 1800s. For the first weeks of the course, we looked predominantly at the prevailing metrical lyrics of the day—at poems by Emerson, Bryant, Longfellow, and others as a way of discovering how radical Walt's poetic departure indeed was.

After his lecture, students would begin their presentations, but Fiedler invariably would interrupt us during the first few minutes of our carefully prepared talks. Ten minutes later he would turn to the student and ask him to pick up where he left off, at least until the next interruption. I gave my presentation on the Calamus poems and, believe it or not, had little support from students on my gay approach to these works. Only Fiedler and a few students supported these readings, now widely accepted in the critical discourse. Later in a seminar paper on "The Sleepers" I received an equally open attitude toward looking at the great American Poetic Icon through a queer lens. Leslie was nothing if not intellectually and socially magnanimous, and I often wondered—as he taught this class on America's most famous poet—if he felt some personal affinity with the author of that "wonderful and ponderous book" that appeared in 1855, the poet who wrote "Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then...I contradict myself/I am large...I contain multitudes." There was something of Whitman's big embrace in Leslie Fiedler.

What better description could there be of a great teacher?

Now that we have recalled a little about Fiedler's life and teaching, we can turn to the work that he produced while in Montana—the work, in other words, that made him one of the most famous scholars and intellectual provocateurs in the nation. And, where better to begin than with his most famous article, the previously alluded to "Come Back to the Raft Ag'in, Huck Honey!" Originally published in Partisan Review in 1948 (his first year back in Missoula after his service in the navy and post-doctoral studies), "Huck Honey!" begins with a Kafka-like precision: "It is perhaps to be expected that the Negro and the homosexual should become stock literary themes in a period when the exploration of responsibility and failure has become again a primary concern of our literature" (413). If this opening does not pack quite the same jolt of the unexpected as, say, the first line of "The Metamorphosis"—"As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect" (89)—Fiedler's gambit certainly gets the reader's attention (even today), and precisely announces the terrain and concerns of his analysis. Fiedler continues:

And yet before the continued existences of physical homosexual love (our crudest epithets notoriously evoke the mechanics of such affairs), before the blatant ghettos in which the Negro conspicuously creates the gaudiness and stench that offend him, the white American must make a choice between coming to terms with institutionalized discrepancy or formulating radically new ideologies. (413)

At work in the late 1940s, Fiedler addresses both white racism and the taboo subject of male homosexuality, and makes clear the cultural and political terrain of his analysis. Unlike some of his peers, he eschews the apolitical, anti-historical, eyes-half-closed, text-only approach of the New Criticism, and sets out the larger issues before he turns to his consideration of Twain, Melville, and Cooper:

The situation of the Negro and the homosexual in our society pose [sic] quite opposite problems, or at least problems suggesting quite opposite solutions. Our laws on homosexuality and the context of prejudice they objectify must apparently be changed to accord with a stubborn social fact; whereas it is the social fact, our overt behavior toward the Negro, that must be modified to accord with our laws and the, at least official, morality they objectify. It is not, of course, quite so simple. There is another sense in which the fact of homosexual passion contradicts a national myth of masculine love, just as our real relationship with the Negro contradicts a myth of that relationship; and those two myths with their betrayals are, as we shall see, one. (414)

In many ways, Fiedler, in his critique of racial and sexual discrimination, and in his heralding of equal rights for both blacks and queers, is ten or twenty years ahead of his time (at least in terms of literary and cultural scholarship), and he approaches these charged issues through the novels then at the core of the American literary curriculum.

So, who would that be on the raft, calling out to Huck? Well, it would have to be Jim, the runaway slave. And what, therefore, would Fiedler be implying about the relationship between Huck, a boy on the cusp of young adulthood, and Jim, a grown man? As his analysis proceeds, and building upon the work of that great English iconoclast, D.H. Lawrence, Fiedler observes that in canonical American fictions, the authors most often pair a white protagonist with a man of color and set them on adventures well away from the company of women. In Cooper's many broken-twig-tales of the ever-vanishing frontier, Hawkeye travels with Chingachgook, that proverbial last Mohican; in Melville's great epic, Ishmael keeps company with Queequeg, a South Sea Islander; in Twain, it is Huck and Jim, at least until the rascally Duke and Dauphin show up and ruin the idyllic life of drifting further and further into slave territory. In effect, Fiedler claims, American white novelists have resorted to these pairings in order to contain, if possible, any implications of homosexuality: what better way to negate any hint of queerness than to hit that taboo with an even more egregious one—at least in nineteenth century American culture—the fear of miscegenation. In 1948, this was radical stuff, and Fiedler clearly wanted to send a few shock waves through the academic community, and beyond. "Huck Honey!" still receives attention today, and scholars such as Constance Penley have pointed to the continuation of this pattern into the twentieth century: the Lone Ranger and Tonto, Captain Kirk and Spock, Maximus and Juba in Ridley Scott's film, Gladiator, and so on.

Not content to rest on this early exercise in critical chutzpah—"chutzpah" remains the term one most often sees in criticism of Fiedler's work—he soon enough turned to what may be his most important, sustained study of American literature, Love and Death in the American Novel (1960). Alongside such works as F.O. Matthiessen's American Renaissance (1941), Alfred Kazin's On Native Grounds (1942), R.W.B. Lewis's The American Adam (1955), Richard Chase's The American Novel and Its Tradition (1957), and a handful of other seminal studies, Fiedler's Love and Death helped shape our understanding of what was then canonical American literature and made clear the obsessions of the canonical male authors. But where his scholarly forebears somewhat politely explored notions of art, nature, and the American self, Fiedler dove right between the sheets (if there were any) and from there to the subterranean reaches of the unconscious and found, in his words, that

The failure of the American fictionist to deal with adult heterosexual love and his consequent obsession with death, incest and innocent homosexuality are not merely matters of historical interest or literary relevance. They affect the lives we lead from day to day and influence writers in whom consciousness of our plight is given clarity and form. Paul Bowles, writing highbrow terror-fiction in the middle of the twentieth century, cannot escape the limitations that plagued Charles Brockden Brown at the beginning of the eighteenth; and Saul Bellow, composing a homoerotic Tarzan of the Apes in Henderson the Rain King, is back on the raft with Mark Twain. (xi)

Fielder finds American literature, in other words, to be a fairly twisted affair, a corpus incapable of exploring adult sexuality and pathologically consumed with subjects, including incest and death, that would make Edgar Allan Poe blush (with happiness, we might presume). Needless to say, his analysis and the connections he makes between literature and culture—were the obsessions of writers the obsessions of most Americans?—offended a great many scholars and readers, but Fiedler called it like he saw it, and too bad for those who took offense. Deservedly, Love and Death put Montana State University on the literary map of America.

No consideration of Fiedler's Montana work, however hasty, would be complete without at least a brief consideration of the essay that most upset folks when it first appeared (and that perhaps continues to upset people, even today), "Montana; or The End of Jean-Jacques Rousseau." Originally published in Partisan Review in 1949, "Montana" decries the plight of the state's Indian population, trapped, as Fiedler puts it, in "open-air ghettos" (23). Traveling across Montana in the 1940s, he finds historic marker after historic marker recounting atrocities committed by whites against Indians; as always, he pulls no punches:

It is at first thoroughly disconcerting to discover such confessions of shame blessed by the state legislature and blazoned on the main roads where travelers are enjoined to stop and notice. What motives can underlie such declarations? The feeling that simple confession is enough for absolution? A compulsion to blurt out one's utmost indignity? A shallow show of regret that protects a basic indifference? It is not only the road markers that keep alive the memory of the repeated betrayals and acts of immoral appropriation that brought Montana into existence; there are books to document the story, and community pageants to present it in dramatic form. The recollection of a common guilt comes to be almost a patriotic duty. (21)

If Fiedler ever worried that such a withering condemnation of Montanan culture might send him the way of Henry Plummer—after all, a page earlier, he visits the history of "the sheriff who was for years secretly a bandit" (20) and who met a bad, rope-swinging end—we cannot say, but he presents a perverse psychology at work in the state. Yet not one to apologize for what he thinks or says, he notes the various public, roadside displays of remorse, but finds them to be empty gestures that do little to redress past wrongs or to undo ongoing discrimination:

The cruelest aspect of social life in Montana is the exclusion of the Indian; deprived of his best land, forbidden access to the upper levels of white society, kept out of any job involving prestige, even in some churches confined to the back rows, but of course protected from whiskey and comforted with hot lunches and free hospitals—the actual Indian is a constant reproach to the Montanan, who feels himself Nature's own democrat, and scorns the South for its treatment of the Negro, the East for its attitude toward the Jews. To justify the continuing exclusion of the Indian, the local white has evolved the theory that the redskin is naturally dirty, lazy, dishonest, incapable of assuming responsibility—a troublesome child; and this theory confronts dumbly any attempt at reasserting the myth of the Noble Savage. (21-22)

In the Montana of the 1940s, he tells us, the myths and realities of the West worked together to reduce the Indian to an abject outcast; the Noble Savage had become the "troublesome child." Although Fiedler's analysis does not, by any means, acknowledge the agency of Montana's first peoples or accurately reflect the complexities of life on or off the reservation—he makes no note, for example, of efforts to protect or recover language, culture, history, religion, and more—and while my point here is not to cast Fiedler as yet another white, male hero looking to rescue the other (he was no mid-century Dances With Wolves), he at least did not shy away from adding his voice to the charged debates on race and culture then taking place in Montana and across the West.

If Fiedler no doubt upset a few Montanans with his dissection of the theater of remorse, he certainly earned a great deal of enmity for his comments, in "Montana," on what he dubbed the "Montana Face" (16):

What I had been expecting I do not clearly know; zest, I suppose, naiveté, a ruddy and straightforward kind of vigor—perhaps even honest brutality. What I found seemed, at first glance, reticent, sullen, weary—full of self-sufficient stupidity; a little later it appeared simply inarticulate, with all the dumb pathos of what cannot declare itself: a face developed not for sociability or feeling, but for facing the weather. (16-17)

Ouch. Although who, precisely, Fiedler had in mind with these remarks on the "Natives of Montana," remains open to debate (his colleagues? Indians? Whites? Ranchers? Missoulians?), he certainly must have known that nearly everyone who read or heard of his reading of Montanans would object to such characterizations by an Eastern, Jewish intellectual who found himself among people who, he thought, "had never seen an art museum or a ballet or even a movie in any language but their own [...]" (17). Although he rather disingenuously remarks, in a footnote later added to the essay, that he had supposed his remarks on the Montana face to be "quite unmalicious," he was never one to back away, and he even leans into the blade in order to give it an extra twist: "the poverty of experience had left the possibilities of the human face in them incompletely realized" (17). While we might ask whether Fiedler was wise or fair or just in making such sweeping, inflammatory statements, I still cannot help but admire his infamous chutzpah. Right or wrong, he most often did not play it safe or hedge or second-guess himself into silence.

If Fiedler was worried that folks might come looking for his job or his head on a platter, he certainly did not let that stop him; as a scholar and social commentator, he was fearless, and if we think back to the repressive, anti-intellectual climate then brewing in the U.S., Fiedler's fearlessness and willingness to address a range of racial and sexual taboos and to risk offending lots of people seem all the more remarkable. At work in the early days of Joseph McCarthy, Richard Nixon, the Red Scare and the widespread distrust—and even active demonizing—of intellectuals, liberals, Jews, homosexuals, and countless other so-called "subversives" or "threats" to the American body politic, Fiedler danced through any number of subjects that could have gotten him into some trouble. Although conservative pundits sometimes like to portray English professors, at least today, as a bunch of radical, no-goodnik pinkos dedicated to dismantling democracy and capitalism one undergraduate at a time, we are, in fact, a pretty tame lot; given his time and place, Fiedler perhaps puts any number of today's tenured radicals to shame.

Yet saying that Fiedler possessed a certain fearlessness misses his best quality: he was smart. True, "Huck Honey!" works as a provocation, but even more it works as a piece of intellectual, literary analysis. Somebody had to ask what these pairings meant, and Fiedler looked closely at the literature that many thought to be the best the nation had ever produced. Likewise, in Love and Death, he was not fooling around or joking; he was serious: what does it mean when a nation produces a body of literature that seems incapable of dealing with adult sexuality, whatever its forms, and that appears obsessed with death? If Fiedler took risks in his subject matter, he took even greater risks in thinking in ways others could not or would not; he clearly enjoyed his jabs at fellow scholars and readers, but he even more seems to have enjoyed trying to change how others read or saw the world, themselves, and their nation. He was an energetic iconoclast, but he was even more a ferocious scholar and thinker, and he opened new ground in the study of literature, gender, sexuality, national myths, and more.

Fielder may have been well ahead of his time in many ways, but in at least one critical matter he was certainly a man of his time; as much as I admire Fiedler, I'm not trying to write a bit of hagiography. As his pronoun choice in "Montana" implies, he suffered from the masculinism that pervaded—still pervades?—American culture in the 1950s and '60s. The Indians and whites of Montana, it seems, are all men, and he pushes women, whether consciously or unconsciously, to the remote edges of the debates and struggles of the era. More, in works such as Love and Death, Fiedler sounds the white, male tradition of American letters—he takes up, at great length, the work of such luminaries as Cooper, Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, Twain, James, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Faulkner, Vidal, Bellow, Kerouac, and more—but ignores the female tradition almost entirely. Stowe rates a few pages, but that's about it; where, one must ask, are sustained considerations of Davis, Jewett, Chopin, Hopkins, Wharton, Stein, Cather, Hurston, and others? Where the readings of Ruiz de Burton, Zitkala Ša, Larson, and more? Like many of the intellectual giants of his day, Fiedler was much more interested in the work of white men than in recovering the work, lives, and writing of women or blacks or Native Americans. Like most of us, perhaps, Fiedler had his blind spots, even as he slashed his way through taboo subjects and posed what were, for many, unsettling literary and cultural questions.

In "The Postmodern Weltanschauung and its Relation to Modernism: An Introductory Survey" (1986), Hans Bertens identifies Fiedler's key place in the early debates surrounding postmodern culture and literature: "Fiedler, who was joined by another American critic, Susan Sontag, found in Postmodernism a 'new sensibility' (Sontag's term), a new spontaneity identified with the American counterculture of the 1960s. In 'Cross the Border—Close the Gap: Postmodernism,' published in 1975, but written much earlier, Fiedler explored further his own brand of Postmodernism, which tended heavily toward pop art" (31). Bertens continues:

For Fiedler—who obviously sympathizes with his Postmodernism—the new sensibility derides the pretensions of especially Modernist art; the postmodern novel will draw upon the Western, upon science fiction, upon pornography, upon other genres considered to be sub-literary, and it will close the gap between elite and mass culture. It will essentially be a pop-novel, "anti-artistic" and "anti-serious." Furthermore, in its anti-Modernist, anti-intellectual orientation, it will create new myths—although not authoritative Modernist myths—it will create "a certain rude magic in its authentic context," it will contribute to a magical tribalization in an age dominated by machines, making "a thousand little Wests in the interstices of a machine civilization." (31)

Bertens' analysis of "Cross the Border—Close the Gap" not only identifies Fiedler's seminal role in the early analysis of postmodernism, but he also notes Fiedler's support (not surprisingly, given his own gift for going against the current) for the contrarian new literature. More importantly still, he shows Fiedler to be an early pioneer in American cultural studies: well before the influence of the Birmingham School had crossed the Atlantic, Fielder championed hybrid, mass, and low cultures, a hallmark of many populist, post-Marxist analyses.

A closer look still at Bertens reveals, at least in part, the hold of the American West in Fiedler's imagination. By the time "Cross the Border—Close the Gap" appeared, Fiedler had been in Buffalo for over a decade, but when it came time for him to characterize the local, provisional truths of postmodern fiction and poetry, he chose the West—Montana?—for his metaphor of isolated pockets of difference, of the denial of ruling myths or metanarratives. If Fiedler put Montana on the literary map, Montana also clearly left its mark on him, and he maintained a life-long interest in what he dubbed "the new Western," or such tales as Jack Kerouac's On the Road and Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Indeed, a number of his later, post-Montana works, including The Return of the Vanishing American (1968), a study of the Western as genre, suggest the lasting intellectual impact of his tenure in the West.

If the West left its mark on Fiedler, he certainly left his mark on scholarly work at the University of Montana. For my own part, I see the ghost of Fiedler in any number of books and articles written by my colleagues. In particular, Bill Bevis's landmark study of Montana writing, Ten Tough Trips (1990), certainly builds on Fiedler's legacy in its mix of the literary, the cultural, and the personal in its analysis of Montana literature and history. Just as in "Montana," where Fiedler mixes scholarly analysis with personal reflection, Bevis approaches his subject both as a literary scholar and as a guy who had been to the same bars as Richard Hugo. As Bevis remarks, "The Montana literature is so various and interesting, and the West is so intertwined with American national identity, that I thought many who do not usually read criticism or history might enjoy hearing a discussion of the books. These are personal essays, then, for a general audience" (ix). For both Fiedler and Bevis, Montana must be approached on the ground; its very materiality, vastness, and cultural and historical complexity cannot, they suggest, be quite captured from the sometimes too-ethereal space of the academy. If traces of Fiedler can be found in Bevis's work on Montana and Western literature, new work by Jill Bergman, Casey Charles, Nancy Cook, Lynn Itagaki, David Moore, and others may well, I suspect, reveal at least a few marks of the great wildman.

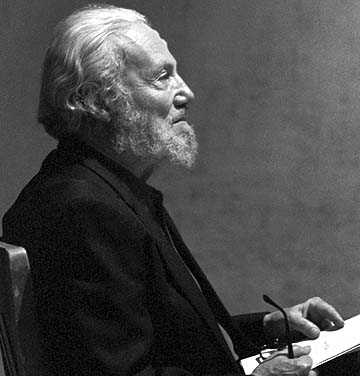

Finally, I have a dream, a way, perhaps, to honor Fiedler's legacy at Montana: alongside the glowering photo of Richard Hugo in the English seminar room—you perhaps know the one, a drink in one hand, cigarette in the other, looking unhappy about something—I would like to see one of Fiedler, the famous one of him in profile, looking like Walt Whitman's younger brother.

Works Cited

Bertens, Hans. "The Postmodern Weltanschauung and its Relation to Modernism: An Introductory Survey." A Postmodern Reader. Eds. Joseph Natoli and Linda Hutcheon. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993. 25-70. Print.

Bevis, William W. Ten Tough Trips: Montana Writers and the West. Seattle: U of Washington Press, 1990. Print.

Charles, Casey. "Re: Leslie Fiedler." Message to the author. 8 Aug. 2008. E-mail.

Fiedler, Leslie. "Come Back to the Raft Ag'in, Huck Honey." Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Second Edition. Eds. Scully Bradley et al. New York; Norton, 1977. 413-20. Print.

---. "Leslie A. Fiedler: Curriculum Vita." Home page. Faculty of arts & letters, State University of New York at Buffalo, 2003. Web. 2 December 2008. <http://wings.buffalo.edu/AandL/english/faculty/fiedler/fiedler_cv.html>.

---. Love and Death in the American Novel. Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1960. Print.

---. "Montana; or The End of Jean-Jacques Rousseau." A New Fiedler Reader. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 1999. 13-23. Print.

---. Preface. A New Fiedler Reader. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 1999. xv-xvii. Print.

Kafka, Franz. "The Metamorphosis." The Complete Stories. Ed. Nahum N. Glatzer. Trans. Will and Edwin Muir. New York: Schocken Books, 1971. 89-139. Print

Penley, Constance. "Feminism, Psychoanalysis, and the Study of Popular Culture." Cultural Studies. Eds. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula Treichler. Routledge: New York, 1992. 479-94. Print.

[The Montana Professor 19.1, Fall 2008 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]