[The Montana Professor 16.2, Spring 2006 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Ann F. St. Clair

Associate Professor, Library Director

Montana Tech-UM

astclair@mtech.edu

The Montana State School of Mines was established in Butte, Montana, in 1900. Today it is known as Montana Tech of The University of Montana. When the school opened, the campus had only one building, now called Main Hall. Its primary purpose was to provide classroom and laboratory space for the school built "to prepare young men for the mining profession."/1/ There was no provision made for administrative offices, nor was there a library.

Even though there was no formal plan for a library, the official printed Announcement of the school's opening indicates that a library did exist in the Geology, Mining and Mineralogy Department. It contained "the leading geological journals" and the department was "building up a library of the most important works on geology, mining and mineralogy."

The history of a small library in a specialized school is less likely to be recorded than those of large institutions, and no such history exists for the Montana Tech Library. As the current Library Director, this history is of special interest to me because today the library faces some of the same challenges that have reoccurred for over a hundred years. Providing appropriate space for the library was an issue when the school began, continued through the decades, and remains a significant challenge today as the library plans a major renovation of its current facility. Understanding librarians from the past helps provide insight about effective library planning today. History also gives me a sense of my place as one among many women who have guided the library for a century. Finally, the library's history is important because it reflects how the university evolved from a mining school to an engineering school, to the four-year, multidisciplinary institution that it is today. The library's past tells an important part of the institutional story, and understanding it helps to direct its future.

This paper traces the history of the Montana State School of Mines Library from 1900 to the present. Using information obtained from the institution's catalogues, newspapers, archival documents, and yearbooks, it examines the library's collections, locations, services, and its line of directors. While the printed sources sometimes contain conflicting or incomplete information, they do provide a unique perspective on the evolution of the library's culture, locations, and personnel. This paper represents phase one of a project leading to a book on the history of Montana Tech Library.

The school opened in 1900, and the First Annual Catalogue indicates that the fledgling library collection contained 27 journals, 4 newspapers, and numerous geological and scientific reports that were kept in the Geology, Mining and Mineralogy Department Library./2/ The person responsible for "building up" the library was Alexander N. Winchell. With a doctorate from the University of Paris, he was the school's first professor of Geology and Mineralogy. In 1901, he wrote scores of letters (archived in Montana Tech Library) to domestic and foreign geological organizations requesting that they send scientific reports and conference proceedings to the school. He also placed the school on exchange lists, thus establishing reciprocal agreements between the School of Mines and outside agencies to send and receive recent scientific publications consistently. This ensured a steady supply of current literature to the school.

Today, Montana Tech Library continues to receive state, federal and foreign documents, and serves as the principal cataloging agent for original documents from the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, which is located on Montana Tech's campus. As part of its historic mining collection, the Library also retains original textbooks, such as the 1894 edition of the Manual of Microchemical Analysis by Heinrich Behrens, used in the first geology classes taught at the school. Textbook titles appear in the course descriptions in the 1900-1901 Catalogue.

The first School of Mines students enjoyed full access to the library materials and the Catalogue notes they were "invited and urged to become familiar with current scientific literature." While some libraries closed their stacks, the mining school encouraged student access. This early precedent for easy access continues today when students login to the library's 15,000 e-journals, 500 online newspapers, and 13,000 e-books anytime from anyplace.

Although the original library was located within the Geology Department, its exact location within the only campus building is uncertain until the 1902-1903 Catalogue confirmed that the department's office and supply room was located in the center of the south side of the building and "contains: a Library of geology and mineralogy." This multi-purpose room also housed rock and mineral collections, ores from mining districts, models of crystals, chemicals, a blowpipe apparatus, and a hydraulic blast hood, oven and a combustion furnace. In a recent conversation, Montana Tech metallurgy Professor Emeritus, Dr. Larry G. Twidwell noted that if the combustion furnace was operational, its heat (up to 1200oF) and emissions would make the supply room a very undesirable place to house a library.

Meanwhile, the collection continued to expand. The 1903-1904 Catalogue notes that the journal subscriptions rose from 27 to 37, and scientific reports and maps continued to arrive from state, national, and international geological societies. The book collection was also growing, especially as the result of a donation from Mrs. James W. Gerard of New York City, daughter of Butte's famous copper magnate, Marcus Daly. She gave the library $300 (about $6400 in today's dollars) "to be expended in the purchase of technical works for the Library." So whether the collection grew too large or the supply room grew too hot, another place was needed for the library.

The 1903-1904 Catalogue recorded that "since the beginning of the year Room No. 5 has been fitted up for the accommodation of the library which heretofore had been scattered though the various departments of the school." This indicates that by 1903 there were several departmental libraries, and their consolidation in Room No. 5 could be considered the first step toward organizing a centralized library at the School of Mines. Although the exact location of Room No. 5 is unclear, it was large enough to hold bookcases, a desk, an atlas cabinet, and a card catalogue with a capacity for "37,800 light weight cards."

Even though the 1903-1904 Catalogue does not name a librarian, some very librarian-like tasks were being done. These included buying books and shipping journals to the bindery. It also noted that "the cataloguing of the library is now in progress and will be completed by the opening of school at the fall semester." There was no information about the cataloger or which cataloging system was being used. Perhaps Professor Winchell was providing these library services.

During the next four years, the Catalogues continued listing titles of books and journals as well as updating contributions made to the library. By 1907, Alexander Winchell no longer taught at the school, but someone was developing the collection, noting in the 1907-1908 Catalogue that the collective holdings "in the library, departmental and others, is nearly 4,000." This is the first time that the number of library holdings was recorded, and it indicated that someone was at least counting the holdings in all of the libraries in the school. In addition, this Catalogue provided the first record of the size of the library, noting it measured "23 by 31 feet." Is this the elusive Room No. 5 described in the 1903 Catalogue?

The 1909-1910 Catalogue documented a historic year for the library. Nine years after its founding, the School of Mines hired its first librarian. For the first time, a name appeared on the faculty list with the title "Librarian and Registrar." Her name was Charlotte Russell. There were no degrees listed after her name. In addition to her librarian duties, Miss Russell registered 50 students that year.

By 1910, the library contained "nearly 9000" publications, more than twice the size of its 1907 collection. Miss Russell reported in the 1910-1911 Catalogue that the library was "located in a large, well-lighted room...is always open to access by the students. The room is maintained by a librarian and offers with its alcoves a cozy, convenient and quiet place for the students' study hours."

Today, in addition to designated quiet study areas, Montana Tech Library provides a learning environment with open spaces and large tables where student teams meet to work on group projects. Conversation is encouraged in a space where, as Montana Tech Athletic Director, Bob Green says, "more is caught than taught," meaning that students learn from one another. The library provides a comfortable atmosphere of collegiality that encourages learning.

The 1912-1913 Catalogue illustrated the tradition of having an inviting library, noting that the library was "located on the second floor of the main building, its windows facing the main range of the Rocky Mountains and overlooking the famous Anaconda Hill." The reference to the "main building" indicated the growth of the school and campus with the addition of a heating plant and an ore-dressing and metallurgical plant which were constructed in 1908. The "Anaconda Hill" encompassed the north end of the city of Butte where head frames and mine shafts proliferated.

Miss Russell continued in her dual role as librarian and registrar for 16 years. By 1919, enrollment had increased from 50 to 191 students. For the next six years, enrollment grew but the amount of library information in the Catalogues lessened, and the collection count remained stagnant at its 1909 level of 9,000. Lack of new information in the Catalogues may have resulted from Miss Russell devoting more time to her duties as the registrar than as librarian.

A notable change during Miss Russell's employment is documented in the 1916-1917 Seventeenth Annual Catalogue where she is listed as an "Administrative Officer" rather than a faculty member. This shift is noteworthy because it signaled a move to differentiate administrators from teaching faculty. It probably does not mean a demotion. Today, my position as Director is administrative, yet I am also a tenure-track, non-teaching faculty member.

Currently, faculty rank for academic librarians varies in universities across the country and in the Montana University System (MUS). At Montana Tech, librarians are required to hold a Master of Library and Information Science degree and are hired at the rank Assistant Professor. They are considered non-teaching faculty because most of the library instruction classes they teach are not delivered as "for-credit" courses. In the MUS, librarians at The University of Montana-Missoula and Montana State University-Bozeman are also tenure track faculty members. However, at all other system libraries including those in Dillon, Billings, Great Falls, and Havre, librarians do not hold faculty rank.

Faculty status is important because librarians contribute to the core educational and research missions of Montana Tech. As faculty members they are required to provide evidence of this contribution as well as those made to the library profession and the community. As noted in the Association of College and Research Libraries Guideline for the Appointment, Promotion and Tenure of Academic Librarians, faculty status "insures that the library faculty and, therefore, library services will be of the highest quality possible"./3/

Although faculty status is sometimes hotly debated, there has never been controversy about the role of the School of Mines library within the community of Butte. During 1924-1925, the last academic year of Miss Russell's employment, the Catalogue included a new entry documenting the collegial relationship with the Butte Public Library, nothing that the public library "is at the service of the School of Mines students." Today there are still reciprocal referrals between the Butte Public Library and Montana Tech Library. In addition, both libraries work toward maximizing budgets by agreeing not to duplicate most purchases. In a recent example of cooperation, at the request of the Butte Public Library Director, Ann Drew, Montana Tech Library donated numerous current books in introductory physics and chemistry to improve the public library's collection in those subjects. The books were donated by the Montana Tech faculty.

In the School of Mines 1925-1926 Catalogue, Agnes E. Hubbard is reported as replacing Miss Russell as Librarian and Registrar. By the end of Miss Hubbard's brief, two-year period of employment, the collection count rose to 10,000 publications. For the first time, the 1927-1928 Catalogue listed the names of the "Committees of the Faculty." Even though there was a Library Committee, Agnes Hubbard was not listed as a member of it. If there was a correlation between this non-participation and her short stay at the School of Mines, school documents provide no evidence of it.

The history of campus committees provides surprising insights about how things change yet somehow remain the same in academia from decade to decade. For example, in 1978, the Head Librarian, Jodi Gouwens, received a memo from the Dean of Academic Affairs, Roy H. Turley, in response to her request to purchase typewriters for the library. Dean Turley noted that "it will be necessary to have the Typewriter Committee approve the purchase of the typewriters." Today, librarians serve on the campus Computer Committee and must get approval from it to buy computers. The technology changes, but the authority of the campus committees does not. Sometimes committees act as barriers to change or represent opportunities to practice patience.

A critical improvement in the library took place after Miss Hubbard left the school. Her librarian position remained vacant, but another Administrative Officer, W. Milton Brown, assumed duties as the registrar in 1928. Then after nearly thirty years, the 1929-1930 Catalogue noted that Margery Bedinger was hired as the first full-time, degreed librarian. She did not also serve as the registrar. Miss Bedinger held a Bachelor of Arts degree from Radcliffe College, the women's educational institution associated with Harvard University. In addition, she was certified by the New York State Library School and was the first librarian hired at the rank of assistant professor. By 1931 she was also a member of the Library Committee.

In the 1930-1931 Catalogue, Miss Bedinger's education and high level of professionalism in library science were evident in her eloquent description of academic librarianship. She noted that "the library at the Montana School of Mines has been organized with the purpose of being as nearly the heart of the institution as is possible." She described the responsibilities of the librarian, stating that "one of the purposes of an engineering education is to teach the students how to use the library and where to look for data when they need it." She was keenly aware of the need to advocate for the library, and she communicated its role and purpose within the academic institution.

In addition to articulating the purpose of the academic library, by 1930 Miss Bedinger completed the monumental task of re-cataloging the 10,000 items in the library. She used the Library of Congress Classification System, common in academic libraries.

Today, with the exponential growth of online journals and books, cataloging systems that work well for printed materials are being reexamined. New systems for accessing electronic library materials are being tested, such as the Remote Data Access (RDA) standard. RDA, developed by the International Standards Organization, is intended to allow multiple database systems to interoperate so users can quickly locate and obtain scholarly information in the electronic format.

Under Miss Bedinger's leadership from 1929 to 1937, the library stacks remained open to students and the "large and varied" collection contained books and journals in the sciences as well as general reference works. This diverse collection was necessary to support the expanding scope of the course of study at the School of Mines. The school developed from strictly preparing "young men for the mining profession" in 1900, to a school with "courses of study designed to give a broad training in all forms of engineering" by 1930.

In addition to teaching students to use the library and giving them access to the stacks, Miss Bedinger invited off-campus engineers to use the library while in Butte. They were assured of receiving help from the librarian. This policy continues today as Montana Tech librarians help inventors to access patent information and regional researchers to locate technical journal articles.

Besides improving access, Miss Bedinger also verified that the library "moved to larger quarters. It now occupies the whole first floor of the south wing of Main Hall, with an additional spacious stack-room upstairs. There is an attractive reading room with large windows on three sides."

The School of Mines President, Francis A. Thomson, officially recognized Miss Bedinger, a quintessential librarian of her time, who articulates the library's role, instructs students, allows access to the stacks, catalogs the collection, fosters community relationships and relocates the library. In his President's Message in the 1932 school yearbook, Magma, Thomson wrote, "I feel there has been a definite enrichment in the intellectual life of our institution. This has been particularly evidenced by increased use of our constantly growing library facilities."

Even though the library expanded to two floors in Main Hall in 1930, as early as 1923 long-range campus planners were beginning to think about constructing a separate structure for the library. The 1923-1924 Catalogue indicated that the "building program for the School of Mines has in contemplation an Administration Hall and Library." Campus planners began working with a local architectural firm, Arnold and Van House, and five years later, the 1928-1929 Catalogue noted that "the building and improvement program conforms to the plan for the development of the campus by Arnold and Van House." A major component of the campus plan was the Library and Museum Building. It was designed to house the library, administrative offices and museum exhibits. It cost $200,000 (about $2.7 million in today's dollars).

Nine years later, planning still continued. A correspondence on March 25, 1937, between Miss Bedinger and Snead & Company, a New Jersey library furniture company, indicated that she was getting price quotations on shelving for the planned building. In a familiar refrain still heard in the university system today, Miss Bedinger laments, "The legislature has given us so little money for the next biennium that any extensive additions or alterations are simply out of the question." Bedinger's successor, Guinevere E. Crouch, assumed the planning tasks. This was indicated in a letter she wrote on September 17, 1938, to the Art Metal Construction Company where she indicated the shelving capacity of the new building.

Finally in 1938, 15 years after planning started, construction began on the Library and Museum Building. It was funded by the State Legislature and the Public Works Administration, a Federal agency created under Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 during the Great Depression as a means of providing employment and improving public welfare./4/

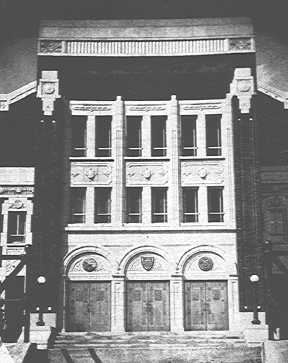

The 1939-1940 Catalogue noted that the new building featured "the extensive use of Gardiner travertine," a light, sandy-colored mineral quarried in central Montana and used for walls, floors, and stairs throughout the structure. Another unique aspect included three sets of bronze entrance doors, a donation from the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. The doors "bear bas-relief panels depicting the evolution of mining methods." The library occupied the entire first floor of the building and contained a spacious reading room, the librarian's office and a map room. The president's and registrar's offices were on the mezzanine floor, and galleries for museum exhibits occupied the third floor. The building was completed in 1940 and the library remained there for the next 38 years.

After the move to the new building, there was a marked shift in the culture of the library. Sometime between 1942 and 1944, all undergraduate students except seniors were no longer allowed direct access to parts of the collection. Instead, students were required to submit title requests to the librarian who then retrieved the requested publication. Libraries have used this practice, called closed stacks, for centuries to protect collections. By the 1940s the School of Mines library owned valuable journals and United States Geological Survey publications. Jean Bishop, Professor Emeritus and long-time Montana Tech librarian, remembers when she began working at the library in 1975 the Government Documents collection was also kept in closed stacks. This was not because it was so valuable, but because space was so limited that part of the Government Documents were stored in boxes, and even librarians had a difficult time locating specific titles. Today, the library still keeps some irreplaceable publications in closed stacks. It is unclear from the Catalogues whether the practice started with Miss Crouch or her successor, Loretta Buss Peck, who came to the school in 1944.

Mrs. Peck was the first librarian at the School of Mines with a Master's degree in science. During her 33 years of service, she achieved the rank of full professor and made enormous contributions by expanding services, developing the collection, renovating the library's space, and serving students.

One former student, 1952 School of Mines alumnus Bob Toshoff, declares in a personal interview that his favorite thing about the library was "the librarian. If I had a problem, I'd start talking and she'd get what I needed. She was a very sincere person. She dedicated her life to that library." He also noted that while living in the dorm, the only telephone was just outside his room. To avoid answering it for everyone on the floor, he took refuge in the library and found quiet places to study.

Mrs. Peck also provided library instruction for students, and posted the hours for sessions at the beginning of each semester. Today, library instruction remains a vital service provided to students at Montana Tech. Librarians collaborate with faculty to develop relevant library assignments directly related to course work.

In addition to Mrs. Peck's dedication to student education, the 1946-1947 Catalogue noted that she joined the regional interlibrary loan program at the Pacific Northwest Bibliographic Center at the University of Washington. This service continues today and provides students and faculty with books, journal articles, films, and other items not owned by the school. Through the pioneering efforts of the recently retired head of the library's Public Services, Julie Buckley, interlibrary loan offers electronic document delivery of articles, many within 24 hours or less.

A significant development during Mrs. Peck's tenure was the advent of the computer. The 1956-1957 Catalogue described an "Instruments and Controls" course in the physics department that used "digital and analog electronic computers." Even though computer use in libraries was not widespread until decades later, this early physics course was a harbinger of the computer's impact which continues today.

In 1965, the School of Mines changed its name to the Montana College of Mineral Science and Technology, reflecting the school's expanding academic offerings. In turn, the library expanded its collection as well as its physical space. Mrs. Peck noted in the 1967-1968 Catalog (note change in title spelling) that "an extensive remodeling project recently completed provides a beautifully designed mezzanine area with additional shelving for 15,000 volumes." The library was also "participating in the current federal program of grants for the enrichment of library resources."

Over the next twelve years, more staff was added to the library. The January 14, 1972, issue of the school newspaper, The Amplifier, contained a story about the new assistant librarian, Miss Jodi Gouwens. However, the 1973-1976 Catalog documented a change in leadership noting that by 1973, Miss Gouwens was promoted to head librarian, while Mrs. Peck, in her 28th year, was the Senior Research Librarian. In 1977 Mrs. Peck retired.

By 1972, the Library and Museum Building was 33 years old. That year, the school's accrediting organization, the Engineers' Council for Professional Development, mentioned in its report that the library was inadequate in its size as well as its holdings. So, plans began to build a library. On March 11, 1975, Fred DeMoney, the President of what is by now called Montana Tech, testified before the Finance and Claims Committee and the Joint Long-Range Building Subcommittee of the State Legislature. In his address he chronicled the long process of rating building priorities within the system, moving from the campus level, to the Board of Regents, and then to the State university system, culminating with the State Legislature. This procedure took two biennia. After years of planning, the 44th Legislature appropriated $1.42 million for the new library. This building was completed in 1978 and provided spacious study rooms and reading areas with natural light. The book stacks were open to all, and there was office space for the eight-member library staff.

Then history repeats itself. Today, the library is 28 years old. The building is filled with books, journals, documents, and maps. The once bright, spacious study areas are dimmed and dwarfed by ceiling-high book stacks. Natural light is blocked, and the library is sometimes referred to as "the bunker." In addition to space and light challenges, there are opportunities for improvement in the heating and cooling system, the roof, elevator, windows, stairway, and furnishings.

The planning process for renovation and expansion of the current facility starts again. As Library Director, I receive sound advice from the Director of Physical Facilities, Rollo Shea, who insists, "You have to have a plan." A committee forms in 2004 composed of campus and community representatives. The Montana Tech administration appropriates $20,000 to fund a plan, and architects come to campus and receive input from students, faculty, staff, and community members about their needs in a library renovation. A plan emerges.

Based on user input, the building project includes a classroom (the library has none) and an updated computer lab. The plan also includes interactive study space with student access to white boards, wireless networks, iPods, tablet PCs, 3-D imaging, scanners, and color printers. A walkway connecting the library to the rest of campus is part of the project. The budget is calculated at $9 million./5/

The library's history indicates some of the stages necessary to construct university buildings. The first library building at the School of Mines took decades of planning before it was funded with State and Federal dollars. The current building required six years of planning before making its way through the Montana University System to the State Legislature where it was funded late in the session. The new plans for the Montana Tech Library Renovation and Expansion are now on file in the University System's Long Range Building Plan. Long-term advocacy is required to guide a project to the level of State funding. Meanwhile, alternative funding opportunities such as private contributions are being explored. Understanding the history of funding building projects provides a realistic context within which to function and persevere.

Tracing the history of this small library in this unique school is important because it reflects how the library evolves as it encounters challenges of collection development, professionalism, and location.

The challenge of developing the collection began in 1900 when Professor Alexander Winchell was "building up" the library. The first collection contained 27 journals, then expanded over 100 years, and now includes 15,000 e-journals. Today, librarians face the challenge of allocating limited budgets between high-demand, costly, electronic resources and printed materials.

The professionalism of the school's librarians evolved over time. The library was started by a geologist, followed 9 years later by a librarian and registrar, and finally, after 29 years, the school hired its first certified librarian. Today, four librarians with master's degrees staff the library, and they must meet the criteria for tenure and promotion.

The library has a long history of changing locations. It began in a storage closet, moved to a room, then occupied two floors in Main Hall. Then it moved to the Library and Museum Building. After 78 years, the library occupied its own building. Today, there is a $9 million plan to ensure its future. This record indicates the need for sustained advocacy to ensure appropriate space.

The library's history reveals the tenacity and resourcefulness of its leaders over the last 100 years. It inspires me to continue building up the library's future.

Notes

[The Montana Professor 16.2, Spring 2006 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]