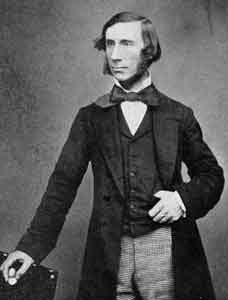

Tyndall in his youth.

[The Montana Professor 23.2, Spring 2013 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Michael S. Reidy

Associate Professor of the History of Science

MSU-Bozeman

John Tyndall died two strange deaths, both at the hands of his wife Louisa. The first was accidental, quick, and relatively painless; the second was deliberate, prolonged, and far more agonizing.

Tyndall's first death occurred in 1893 on a cold December day in Hasslemere, south of London. The seventy-three year old physicist lay awake in his bed as the dim light of dawn filtered into his bedroom. Bottles littered his bedside table—sulphate of magnesia for his intestines and chloral hydrate for his insomnia. At 8:30 in the morning, his wife Louisa, twenty-five years his junior, came to his side to comfort him. He requested some magnesia, a mere spoonful, which she poured from one of the bottles and brought carefully to his lips. It tasted curiously sweet, he thought. Louisa panicked. She had accidentally given him chloral, an extremely powerful narcotic, killing one of the greatest scientists of the Victorian era./1/

Tyndall's second death was even more bizarre. Louisa, devastated by her tragic error, concocted an unwittingly devious plan to bring her husband back to life. She would take control of all his journals, collect all of his correspondence, read all of his unfinished writings, and bring everything together in a monumental Life and Letters. Wracked by guilt, she devoted her life to gathering all of his materials. Whatever letters she collected she kept under wraps, intending to make them available only after she had completed her biography. For forty-seven years she toiled. Yet, year after year passed with no Life and Letters. When she died in 1940 at the age of ninety-five, she had published nothing to resurrect the life and work of her long-dead husband. He slowly faded from memory. With Louisa's grief and guilt, and with her failed promise of publication, Tyndall died a prolonged, lonely death—taking Louisa's grief and guilt with him.

Tyndall's drawn-out second death partly explains why his fascinating life has been so largely overlooked. When other eminent Victorians passed away, their multi-volume Life and Letters soon followed: Charles Lyell's in 1881, Charles Darwin's in 1887, Thomas Huxley's in 1902, Herbert Spencer's in 1908, and J. D. Hooker's in 1918. Victorians used these publications both to make sense of death and to foster a new, textual life. It is also to these collections that historians first turn to continue the act of resurrection. Sadly, Tyndall's first biography did not appear until 1945, and though it included selections from his personal correspondence, the letters had been heavily expunged of all things unpalatable. By then, the lack of a standard Life and Letters had already obscured Tyndall's place in the history of science and culture.

Before Tyndall's double death, he had lived several interconnected lives. The first was spent primarily in an attic surrounded by scientific instruments of his own design; the second either in front of fashionable audiences or behind the scenes, directing and popularizing the sciences of the day; and the third either alone or with a trusted guide, suspended precariously on the sides of high, alpine cliffs.

Born in Ireland under relatively poor circumstances, Tyndall became one of the most influential experimental physicists in the Victorian era, rising through the scientific ranks to succeed the legendary Michael Faraday as the director of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, one of the premier scientific positions in England. Tyndall undertook most of his sophisticated experimental research in the cramped attic of the Royal Institution. He became fascinated with the topic of radiant heat, particularly the manner in which atmospheric gases absorb infrared radiation. While nitrogen and oxygen were largely transparent to infrared radiation, he found that compound gases, such as carbon dioxide and water vapor, were relatively powerful absorbers of heat. The significance of this struck him immediately. In his paper to the Royal Society of London in 1861, he announced, in astonishingly prescient terms, that any changes to the constitution of the atmosphere "would produce great effects on the terrestrial rays and produce corresponding changes of climate…. Such changes in fact may have produced all the mutations of climate which the researches of geologists reveal."/2/ This was the first experimental confirmation of what is now known as the natural greenhouse effect.

Tyndall's life as an experimental physicist overlapped with his second great life's work. He became one of the most outspoken advocates and controversial defenders of science in the nineteenth century. It was through his public lectures at the Royal Institution that fashionable audiences in London experienced the latest revolutionary discoveries in the burgeoning fields of physics and chemistry. His flamboyant lectures mixed practiced showmanship with extravagant experiments to present science as an exhilarating spectacle.

Tyndall's prominent position as a public lecturer contrasted sharply with his work behind the lecture curtain, where he deftly defended science from its religious critics. In this, he was more combative than eloquent. Along with biologist Thomas Huxley, philosopher Herbert Spencer, and botanist J. D. Hooker, Tyndall argued that naturalistic rather than theistic explanations could (and should) account for the workings of nature. He unflinchingly held forth as a leading figure in the debates over evolution, representing the powerful group of intellectuals who defended Darwin and his naturalistic worldview. He is often remembered for two debates in particular. In July 1872, he called for an experimental verification of prayer, embroiling himself in what was referred to as the "Prayer-Gauge Debate." American Methodists, in particular, were outraged; they set up prayer meetings in all the major cities on the East coast to pray for "poor" Tyndall's soul./3/

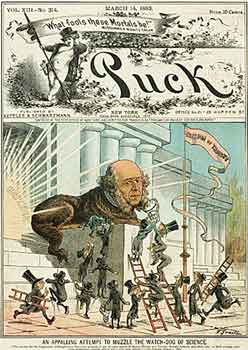

The second, more acrimonious debate followed directly from Tyndall's presidential address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Belfast two years later. Tyndall praised Darwin's accomplishments and dramatically declared that men of science "shall wrest from theology the entire domain of cosmological theory."/4/ The speech scandalized Christian clergymen and intellectuals, who responded with numerous pamphlets, newspaper editorials, and journal articles. In the press, he was satirized as the spokesperson for science who some believed needed a muzzle.

Tyndall's third life was confined to the lofty altitudes of the Swiss Alps. He was one of the figures largely responsible for the growth of mountaineering as a sport, a pioneering alpinist during the "golden age of mountaineering." He spent almost every summer from 1854 until his death in 1893 turning the Alps into what Leslie Stephen famously called "the playground of Europe." His scientific colleagues admonished him for brazenly putting his life at risk. He climbed Mont Blanc several times, spending twenty hours on the summit after his third ascent, longer than any other person had dared to remain on top of Europe's highest peak. He was also the first alpinist to study the approaches to the Matterhorn, narrowly missing the first ascent. He was the first to turn the mountain into a pass, climbing the more difficult traverse up the Lion's Ridge from Italy and down the Hornlike Ridge to Switzerland. Even more astonishing (and controversial), he made the first solo ascent of the Monte Rosa, Europe's second highest peak. At the time, climbers were called "amateurs" because they were required to hire professional guides, so Tyndall's solo ascent helped pioneer guideless climbing while earning him the wrath of the climbing community.

His crowning achievement in mountaineering took place on August 19th, 1861, when he made the first successful ascent of the majestic Weisshorn, a solitary snow-covered peak in the Pennine Alps. At 4504 m (14,780 ft.), it was a daunting prospect, with crevassed glaciers at the beginning, rock and ice bands in the middle, and a massive fifty-degree pyramidal snow slope guarding its upper reaches. Tyndall began with his guide J.J. Bennen and porter Ulrich Wenger in the small town of Ronda, bivouacked mid-way up, woke at 2:15 the next morning, and—with a flask full of wine and a bottle of champagne—reached the summit in twelve hours. "The work was heavy from the first," Tyndall boasted, "the bending, twisting, reaching, and drawing up calling upon all the muscles of the frame."/5/ He returned to England a hero, one of the reasons why his name lives on in mountain ranges, peaks, and glaciers throughout the world, from Europe and North America to Africa and New Zealand.

Tyndall's influence reached far beyond Britain, producing an enormous international network of scientific colleagues stretching from England to the Continent to America. But lacking a Life and Letters following his death, his influence on subsequent generations has been minimal—until now. Taken together, his recently examined letter archives hold the promise of opening a new window of understanding into significant aspects of Victorian science, society, and culture.

Montana State University is at the center of resurrecting Tyndall's life and work through the John Tyndall Correspondence Project, a large-scale, international "big history" collaborative project that will eventually publish more than 8,000 of his letters in twelve volumes. The first volume will appear next year, with subsequent volumes following every six months. The Project includes two other general editors, twenty-four volume editors, and over sixty transcribers working in four countries on three continents. The process of collecting, digitizing, transcribing, and editing these letters has galvanized a large, international community of scholars at various stages in their careers around core themes in the history of science and culture.

As is the case with other correspondence projects, such as the Darwin Project, the Tyndall endeavor has already led to new research trajectories, requiring scholars to significantly revise their perspectives on 19th-century science. For example, I have found in his letters evidence of how he viewed the relationship between his scientific research and his mountaineering exploits. He deliberately formulated most of his research programs based on his ability to climb mountains, consistently performing experiments and comparing observations made at different elevations. His letters also have shown the close link between his alpinism and his growing agnosticism. The height of his climbing came in the early 1860s, the same time he was formulating his agnostic views. Mountaineering enabled him to experience nature firsthand, to see its laws in action. Yet, for Tyndall, there was always something more to nature than laws. In the Alps, he experienced an otherworldliness that he never found in a religious setting and could not search for in a scientific laboratory. On the sides of mountains, Tyndall found a worthy replacement for his lost faith.

If the planet were not warming, turning the natural greenhouse effect into global warming, the new climatology center in Britain, the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, would not bear his name. And if the debates over evolution were not still being fought, his staunch defense of naturalism would not resonate so clearly. As interest in Tyndall continues to grow, and as his life and work continues to sound prescient to modern ears, we will keep discovering in his correspondence fresh answers and exciting new possibilities for future research.

Tyndall always loved the mountains, a passion he shared with his wife, Louisa. Together, they built a summer home in the Swiss Alps. I think he would have loved the mountains of Montana as well; I wish he had visited the Rockies before his untimely death. As he lay in his bed in Hasslemere that cold December day, the taste of chloral hydrate sweet on his lips, I also wish I could have whispered in his ear to tell him just how exciting his long overdue resurrection would ultimately be.

Notes

[The Montana Professor 23.2, Spring 2013 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]