[The Montana Professor 15.2, Spring 2005 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Gary Funk

Music

UM-Missoula

Robert Hoyem

Independent Scholar

Missoula

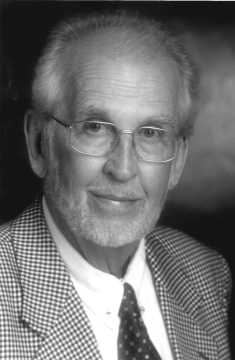

John L. Lester was head of the voice department of the School of Music at The University of Montana-Missoula from 1939 to 1970. He served as Dean of the College of Fine Arts from 1970 to 1972, whereupon he retired from the University's faculty. During his tenure at UM Prof. Lester was one the faculty's most distinguished members and one of its most respected teachers. His reputation as a voice teacher was indeed world-wide, and, remarkably, only increased after his retirement.

In this article we attempt to present a portrait of this very important figure from the UM faculty's past. We do so partly out of reverence--we both had the privilege of studying under John Lester/1/--but more out of hope that others may benefit from knowing his work, if only indirectly. Fortunately, Prof. Lester left a voluminous collection of materials at his death in 1994. These include personal notes, letters, scrapbooks, a set of National Public Radio recorded interviews, recorded interviews conducted in Germany by Hoyem, and a videotaped interview recorded in Seattle. It was Prof. Lester's intent to write a book about his vocal pedagogy and its sources in his life experiences as student, singer and teacher. We plan to follow this article with a comprehensive book dedicated to his life and teachings, thus fulfilling, as best we can, Prof. Lester's own desire. We are greatly pleased that the nature of the material Prof. Lester left us often enables us to allow him to speak for himself in this article.

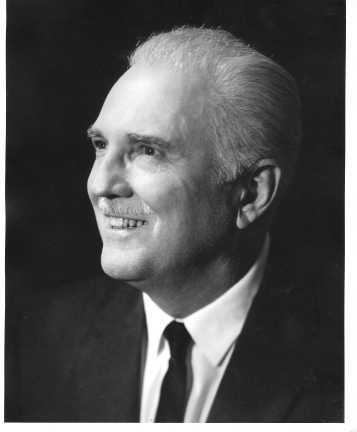

When voice students knocked on John Lester's studio door at the University of Montana, they were greeted by a firm baritone voice calling out, "Come in!" Upon entering the studio, a student would see a strikingly handsome and well-groomed man who seemed taller than his six feet. By the 1960s, his neatly combed hair was white and his well-trimmed moustache helped to define his John Barrymore-like face. He would stride to the piano and sit down on the bench, slinging his left leg over his right and putting his hand on the keyboard, although he was not a piano player, except for negotiating simple vocal exercises. His smiling eyes appraised a student with interest and encouragement. The slight odor of his morning cigar from the drive to work lingered on his clothes.

An anatomical model of the larynx, and one of the human head and neck rested on his piano, along with a book or two on singing technique. Hanging on the wall were approximately 20 photographs, some of which were of former students who had gone on to prominence. Lester's stepping out of the office gave students the opportunity to study the photos up close and read the autographed notes of sincere appreciation that were scrawled on them. New students could sense the significance of these for their own studies in that room. There was also a collection of glass-framed pictures of singers from years past, among them a young, costumed opera performer named Giovanni Luccari (John Lester).

When Prof. Lester would return to find a new student gawking at the old pictures on the wall, he might point out, "That one just to the right was my voice teacher, Jean de Reszke, one of the greatest dramatic tenors around the turn of the century before Caruso."

In the voice lesson, John Lester worked technically, above all. He would begin each lesson with a concentrated warm-up of the student's voice. Because building the voice begins with the encouragement of good singing habits, it was partly through this process that he established a framework upon which reliable technique could be developed.

Before the lesson, Prof. Lester had already been thinking about the student's voice for some time. If it was a warm summer morning, Lester had likely already played 18 holes of golf before he stepped into his office, and students might have imagined him mulling over their vocal concerns as he walked the fairways of the Missoula Country Club. He would often interrupt a scale mid-ascent and say something about the quality of the sound, then make a technical suggestion related to the position of the larynx, the posture of the jaw, or physical coordination of breath energy. With his fully resounding production of tone, Lester would demonstrate the sound that he wanted the student to produce. The student would then attempt to imitate this sound, usually paling in comparison. In his later years, his ability to sing a brilliantly baritonal high b-flat would impress even his best students.

John Lester found that students needed to recognize quite consciously that they sounded as they did because their ears expected the voice to which they were accustomed. If they were to improve, they had to be willing to experiment with changes to their sound, or their vocal limitations would remain. Lester recommended that students think of a sound that would require the throat to be open. If they did so, they would often experience that their larynxes dropped while their throats opened. If proper adjustment was not achieved, the student would be asked to touch Lester's larynx to provide an opportunity to feel its lowered position as he demonstrated the open-throated sound again. The student would then attempt to imitate Lester's technique. If a better sound was produced, he would continue with repetitions of this improvement to help the student firmly register what had just been accomplished. Sometimes, Lester would pick up a book opened to a particular page and ask the student to read a text which addressed the same vocal problem.

He believed that vocal problems could only be solved by students being willing to accept the necessary re-training of muscles not accustomed to proper technical functions--including those related to correct breath management. Lester taught the singer to become an active instrument builder who built the voice through the well-coordinated manner in which the breath was taken, encouraging expansion and flexibility of the resonating space. Thus, the breath could be properly applied to produce resonant vocal sound. It was on the basis of John Lester's directly pragmatic approach to teaching that his students became secure in managing their technique for vocal artistry.

When John Lester arrived in Missoula, Montana, in the late summer of 1939, he had studied, sung opera and taught in Europe for seven-and-one-half years, then maintained a teaching and recording studio in New York City for 10 years before accepting a position as head of the voice department of Montana State University's School of Music./2/ He was born in Mt. Healthy, Ohio, but moved with his family to Texarcana, Texas, when he was six years old. There he completed high school and then his education and training at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, where he earned a BM in voice and a BA in English with a minor in French.

After a short period of voice studies in New York with the well-known baritone and pedagogue, Oscar Seagel, he sailed for Europe where he studied with Seagel's great mentor, Jean de Reszke in Nice, France. De Reszke, who was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1852, had been considered one of the greatest dramatic tenors of the age, and in retirement had also become a remarkable teacher whose fame drew advanced students and young professionals to studios he maintained in Nice, Milan, and Monte Carlo. John Lester was his student until de Reszke died in 1925.

Lester, who bore his family name, Luechauer, adopted the name Giovanni Luccari for a "limited" career as a lyric baritone in Italy, where he also studied with the internationally renowned character baritone, Mario Sammarco in Milan. Sammarco, one of the most outstanding figures in the vocal history of the early 20th century, was a colleague of the great Enrico Caruso in Milan, and for many years, a leading baritone at Covent Garden in London and at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

During his studies with de Reszke in Nice, John Lester also began teaching voice there when he was only 23 years old. "I discovered that I had a peculiar talent for helping people who had been studying voice four or five years longer than me, and I eventually got the reputation in Europe for being able to help people who had lost control of their voices."

In 1929, Lester returned from Italy and went to New York City. By then he had also experienced the growing political disaster in Berlin, coaching there for three months with the leading Lied accompanist of the time, Michael Raucheisen. In Italy, "those were the days of Mussolini and it was difficult for singers. As Giovanni Luccari, I would have had to sign an oath to support the Duce with my 'life's blood.' Well, I couldn't do that! In New York, I started a voice studio with students who, to my surprise, had already heard about me. The world of music was relatively small back then."

For professional reasons, John Lester Luechauer changed his name to John L. Lester in 1930. Along with his work as a voice teacher, he appeared as a concert, church, and NBC radio soloist. Teaching in New York until 1939, he taught vocal production for the Paramount School of Acting, and trained performers in radio, musical comedy, opera, concert, and nightclub entertainment. Among his prominent students were Joan Marsh and Jane Froman (20th Century Fox actresses), Frank Luther and Andrew Shea (NBC radio singers), opera singers Sonia Sharnova (Hurok Opera Co.), Brooks Dunbar (Philadelphia Opera Co.), and John Patrick (Chicago Civic Opera Company)--and even sports celebrities, such as national tennis single's champion Alice Marble.

In 1932, Lester married Willa Rickard, actress, dancer and Hattie Carnegie model. Priscilla, the first of their two daughters, was born in 1938.

"By 1939, I was beginning to think of applying for a university teaching position. Life in New York was interesting, if expensive, but the pace was terrific, hard on the nerves--not worth it. It's also difficult to take care of a baby daughter, living in the very center of New York. I wanted to find a place where she could see a blade of grass occasionally.

"I began receiving letters written in longhand from a man named Crowder, who was the Dean of the School of Music at Montana State University in Missoula. Dean Crowder impressed me as being a real human being, and I felt that he was a person I could work with. My New York friends told me that Montana was no place to go for a man of my ability and experience. But moving to Montana was the best thing that ever happened to me!

"University teaching provided me with the opportunity to work consistently with students for four years, being able to lay a vocal foundation in getting people built up so they could be recognized even outside of Montana. Working with operatic voices in the studio and in the theater gave me a terrific amount of experience. It was an ideal way to teach--a real learning opportunity."

In the fall of 1939, John Lester had only been in his new position for a month, when the University student newspaper, the Montana Kaimin, published an article on October 20th:

The last operetta produced at the University was The Desert Song in 1934.... Now is the time for the student body to demand a musical show--if you do, you'll get it!

Only three days later, a letter from Dean Crowder and Lester appeared in the Montana Kaimin, making the offer that if student response justified it, they would make operetta productions coursework for which academic credit would be granted.

Acclaimed as the most successful University function of the year, the "All-University" production of Sigmund Romberg's The Student Prince played to capacity audiences on May 2 and 3, 1940.

In 1941, The Vagabond King was produced, involving some 110 students./3/ The Montana Kaimin proclaimed, "To make the premiere the glittering affair it should be, program handlers will have giant searchlights stationed near the auditorium. A special marquee with clusters of bright-colored lights is to be erected above the auditorium entrance." The Missoulian reported, "Playing before a packed and enthusiastic house, the cast took eight curtain calls."

In addition to these productions, it was through his regular semester recitals and solo performances for community service clubs and state events, such as conventions and fund-raisers, that Lester established his reputation as performer and citizen.

Once established, a two-year cycle of operetta productions continued, with the exception of three years during WWII, when there were too few male students to make up a full cast. By the 1949-1950 academic year, John Lester, in continuing collaboration with the University Department of Drama, was able to prepare the first-ever opera production in the State of Montana--Rossini's The Barber of Seville. Two years later, this tradition was established with the production of Puccini's La Bohème.

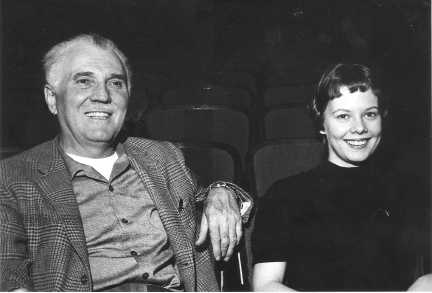

Thus, John Lester continued his remarkable career in establishing himself as a moving force for the School of Music and the University. Among his many students who went on to international acclaim in concert and opera, his second daughter, Joanna, born in 1941, enjoyed a successful professional career as a versatile soprano, actress, and dancer in show entertainment, musicals, and eventually as a leading soprano in German and Austrian opera theaters.

"From 1939 to 1970, we had many good voices in Missoula, and my students, Judith Blegen and Ron Bottcher went on to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. I started teaching Judy when she was 16 and she studied with me during her high school years."

Judith Blegen Gniewek, January 5, 2005:

I have many fond memories of John Lester. He was my church choir director as well as my first voice teacher. His daughter, Joanna, was my classmate and friend throughout high school. In fact, we frequently got ourselves in trouble with her dad because of our giggling during services. I am grateful to Mr. Lester for opening up the world of singing to me. He taught me the necessary basics, which set the foundation for my conservatory years at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There, of course, I was guided to refine my vocal technique, study foreign languages, and prepare for the challenges of the professional vocal scene. Fortunately I was well prepared and went on to have an exciting, successful career in opera, recitals and solo appearances with the world's greatest orchestras and opera houses. Now, in my retirement, I reminisce and am grateful for those formative years with John Lester.

Throughout his tenure, Prof. Lester established himself as a pillar of the Missoula community, and was a well-known visitor throughout Montana. He took the University to the people, with his student ensembles performing everywhere from Hamilton to Helena to Harlowton, from Butte to Baker.

In response to the 1964 twelve-city Montana State Centennial tour of Puccini's The Girl of the Golden West, Charles W. Bolen, Dean of the School of Fine Arts, wrote: "Without a doubt, The Girl of the Golden West has been the highest quality performance of anything I have witnessed since coming to Montana State University. It has been nothing short of an artistic triumph!"

What made operatic successes such as these possible was Lester's consistently strong work in the studio, working with students from 8 a.m.-5 p.m. each day, building the vocal technique and musical artistry required to sing difficult operatic roles.

Certainly, one of John Lester's major accomplishments can be seen in the kind of intra- and inter-departmental dialogue and collaboration he was able to foster over the many years of successful and richly educational "All-University" productions of operettas, musicals and major operatic works. As a remarkable testimony to this collegial cooperation, it was the chairman of the Department of Drama, Bo Brown, who gave the following tribute to John and Willa Lester on February 19, 1965:

What does an artist in Montana accomplish in a life-time here, removed as we are from the great halls of success? For a teacher of John Lester's caliber, the accomplishment is people, the taking of young, untrained, but exciting talent, and giving it early and definite shape for a future of artistic accomplishment. The richness of such a life lies in the...glowing spirits of those young men and women, to whom John Lester has imparted the joy of artistic awareness.

The answer also lies in the way of life that John and Willa have built for themselves and have shown to us, a way filled with understanding, thoughtfulness, order, and artistic integrity tempered by human forgiveness. The teaching has not always been easy...but the purpose has always been right, and those of us who have had the privilege of living and working in your presence are indeed richer people.

For 33 years, from 1939 until, 1972, John Lester was not only a member of the University's School of Music faculty, he was also prominent in vocal music pedagogy's most important professional organization. He served on the Board of Directors of the National Association of the Teachers of Singing (NATS) for twelve years, and was also regional governor for the Northwest Division.

Thus, Lester also became nationally known through his publications and lectures on voice teaching issues, as well as through the accomplishments of his students as ongoing professionals. As his reputation became increasingly known among American professional opera and concert singers in the U.S.A. and Europe, John Lester's studio in Missoula, Montana, became a place to go for vocal help--as his studio in New York City had been in the 1930s.

"Students come to you to develop their talent, but I also teach them to recognize the problems associated with the singing profession. Some people have talent but, when you put them on the stage, they don't have the ability to capture the audience, or the temperament to deal with the difficulties in the field.

"If they haven't the courage, determination--something inside them to make them successful--they'll not make it. They need such strong devotion, something in the heart, a willingness to do what a student should do! Never do I say, 'You should go into the field.' But I don't discourage either. I believe that students have the right to try!

"After you have them for a few lessons, you can tell if students are going to be able to think vocally. You sense a musicality--a manner of handling a phrase to give it meaning, of handling the language to make it expressive. Within three months, you can usually tell what they're going to be able to do, but you can't be sure if they have the fortitude.

"You give students exercises to see how they do with the native, untutored management of their voices. If they have a song they're singing, you can tell a bit about their musical sense, but you have to see if they'll respond to what you're trying to teach them. They have to have enough humility and enough confidence. If they are overly confident, that's sometimes a good thing. Those students may plow right ahead, whereas another person is timid about it.

"Although you can teach musicality to a certain degree, a teacher shouldn't be discouraged if, at first, the student seems a little bit slow to learn. Talented persons, who learn more slowly than others, may realize they have to keep working to take care of all the details. Persons who seem to catch on very quickly, sometimes get the feeling that they really know more than they do, and don't want to work harder to learn the fine points. Unless students are willing to be very picky about it, they sometimes can't sense the meaning of the language and express it in the vocal line.

"I've had pupils who, I've been told by their teachers, have perfect technique. I never say that students are perfect, because the minute they think they don't have something to improve, they fall back. A student must be constantly working.

"I've seen people who have good vocal material, but they can't accept change or training. For students who don't have the musical sense, but dream of becoming a singer, I must show them where they cannot yet do things. If I discourage them directly, they may go to somebody else. We have lots of voice teachers in this world, I'm sorry to say, who will accept such people, take their money and encourage them unduly over a long period of time, knowing that they're going to frustrate themselves.

"I have no quarrel with any teacher, with any system, as long as the teaching is honest and gets results. If a student is incapable of applying instruction and failing, my duty is to point that out. But I never say, 'You can't do it.' I say, 'You are not doing it.' I find that works better. One should be as honest and straightforward as possible."

Prof. Lester's intent was always to remain as direct as possible in clarifying for his students the function and coordination of the voice. That was how he taught.

In the following account of Prof. Lester's approach to teaching we present some of his most perceptive descriptions of salient aspects of vocal technique. No account of Prof. Lester's work would be complete without inclusion of this material. We have endeavored to select statements from the materials Prof. Lester left us that will enable non-singers to appreciate the difficulty and complexity of the art he taught so successfully. We resume our biographical account of John Lester's remarkable career in our concluding section, Retirement Years.

"The human voice produces beautiful musical sounds with a range of as much as three octaves. It is sometimes a bit intimidating for a voice teacher to take the responsibility of attempting to help a singer control this instrument. The voice teacher must try to train the singer's ear, and hope never to confuse the native coordination. Considering the complexity and sensitivity of this sound-making instrument, it is remarkable that many vocalists, without the aid of an instructor, sing so true to pitch with a beautiful sound. People generally think that we are born with a fine voice and then just sing at 16. But the control of the full range of the voice is rarely found without instruction.

"Many young singers feel that one or two hours of practice a day is enough. I think that is very sad. There is so much that students can do! They should gain a reading and working ability with languages. They should work on articulation. Singers need to develop physical posture, how they should carry themselves, how to handle physical expression. One could spend three to four hours a day working on how to get the voice into position to present it. The work a vocalist must do is as great as the work on any instrument!

"Voice students should gain reasonable knowledge of the physical structure of the vocal instrument and how it functions. Students should be made aware that the vocal instrument has three components: (1) a physical force; (2) a vibrating element; and (3) a resonator. All three parts can be manipulated. By changing the shape of the throat, for example, we can produce a limitless number of sounds. The voice is a very flexible thing.

"I work with managing the breath, the larynx--or voice-box--and the resonating space. The sound and the ear of the singer are equally important. If singers can conceive sounds and produce them, that is all they need, really. If they can't do this, they have to find ways to change how they make sounds."

"Inhalation of air is caused by the expansion of the body, and exhalation is the blowing out of the air via the contraction of the body. The combination of the natural rise and fall of the diaphragm, along with the expansion and contraction of the lower ribs at the sides and back of the body, is best for supporting speaking and singing. For this to occur, a comfortably postured chest is important.

"Students ought to know that, to sing, they must have a certain degree of flowing breath pressure to activate the vocal instrument--the vocal cords in the larynx. It is well to realize that so-called 'support' is not only muscular strength, but the proper degree of breath pressure applied to the vocal cords. There is an amount of air flow and breath pressure which will cause the vocal cords to vibrate most generously and easily. If you don't get enough breath passage or flow, you don't get your most beautiful sound. When the pressure is too great, discomfort will be felt in the throat. Too little breath pressure may cause a tone to 'crack' and the vocal range to be impaired. The goal is to discover the amount of breath passage that causes the vocal cords to vibrate best and create the most resonance. The combined movement of the diaphragm and stomach muscles, along with the sustained expansion of the ribs, helps to eliminate unnecessary chest activity and constricting tension in the throat."

"The larynx in the throat houses two vocal cords which are connected in the front and back of this voice-box. To activate the cords one needs, first, the desire to express oneself vocally and, second, the application of flowing breath under compression. Any suggestion is worthwhile that brings about better coordination between breath supply and the action of the vocal cords, causing the singer to produce a more resonant sound with less apparent effort. The position of the larynx affects the ease with which the vocal cords function. Almost any change in the vowel color is a result of a change in the laryngeal position. When the cords function best, the focus of tone is quite defined and easily perceived. I believe that one must acquire the ability to sing with a comfortably lowered larynx.

"Most beginning singers, because of speech habits, have the larynx too high to allow for the freedom of the cords throughout the entire range of the voice. To influence the singer to get the proper larynx position, I work with the student's concept of vowel color. A white or flat vowel color tends to raise the larynx; a dark, round vowel tends to lower the larynx. One can also achieve a relatively low laryngeal position by yawning slightly.

"Once these concepts have been established, I find it is important, however, to take the singer's mind off of the physical action and, instead, focus the attention on the quality of the vowel, sound and ease of production. A singer must go beyond the concept of the physical. One should think of the timbre of the voice, the artistic use of the voice, the feeling of comfort and freedom of expression, which are made possible by acquiring a properly lowered, while flexible, laryngeal position."

"The resonator consists of the spaces just above the larynx, behind the tongue, as well as the mouth and the nasal passage. This 'tube' for vocal sound is only about eight inches long and needs to be rounded and opened through expansion. For the well-projected voice, this opening of the throat is very important and will result in a lowered larynx. Resonance and tone quality are affected by the shape and size of the resonating space.

"I have a 'concept of opposites.' You can make the voice too bright or too dark--somewhere in between is the beauty. I'm not afraid to experiment. I'm not afraid to have students try the seemingly most disagreeable, ugly sounds. Once they know and feel how that is done, they will know when they get it correctly. Our learning process is as much learning from mistakes. In fact, maybe we learn from our mistakes more thoroughly than we do from any other source."

"Teaching of the voice involves many interesting procedures. Some, I think, are worthless, but many of them are excellent. I could categorize three approaches to teaching voice. In the first place, there are those teachers who work primarily by imitation, by sound and placement and getting the voice into the head. Some say, place the voice in the nose, some say in the forehead, the top of the head, the back of the head, in the chest and so forth. Well, the voice, of course, is involved with all of those.

"There is second type of teachers whom we call scientific. They work with the position of the larynx, all of the muscles involved with the breathing process, and so forth.

"Then there is a third type, using the sense of sound, placement, vowel colors and that sort of thing, who are also sufficiently scientific. I belong to this category.

"I had no teacher who taught like any other teacher, and still they were all successful. But I became known as the man who could help singers, because I worked directly with the larynx, the throat, the breathing system and the sound. The sound is most important! The ear of the singer is most important! If they can hear the sound, that's all they need, really."

In a 1982 interview conducted by William Marcus of KUFM for National Public Radio, 81-year-old John Lester described his activities in retirement:

"Since my days on the faculty at The University of Montana, I've been going to Europe, where I teach opera singers entirely. I teach at Covent Garden in London, Milano and other cities in Italy, in France, Austria, as well as in Australia and the Philippines. I've worked with singers such as the sopranos Marilyn Zschau and Barbara Bonney, who are well known all over the world; the baritone Barry Mora, and tenors Tony Gonzaga, Donald George, and José Lima, who sing in many of the great opera houses."

Having been chosen to receive the 1983 Governor's Award for the Arts, John Lester responded:

"I am proud and pleased to have my work recognized by the Montana Arts Council, by nominating me to receive the 1983 Governor's Award for the Arts. Thank you for the invitation to attend the awards ceremony. However, I must be in Verona, Italy, helping opera singers from January 15 through February 15, and then in London with Marilyn Zschau, who is singing the lead role, Minnie, in the opera La Fancuilla del Oueste by Puccini."

Marilyn Zschau, January 6, 2005:

Frankly, I would have possibly had NO career at all without John Lester's training in the use of my voice for opera. In my opinion, he was unique, in that he could train a singer to project the voice so that it would resonate and be heard in a great hall over a large orchestra. In my case, this included teaching me to believe in myself as a Dramatic Soprano, and that I would be able to sing Wagner's Brünnhilde. This I did, to my very great delight, and his training of my voice also enabled me to be heard over the largest orchestras, led by conductors who might have been criticized for not being able to keep the volume level down!! Because of John Lester's vocal training, I have been very successful in the world of opera, and have sung one of the most demanding roles, Richard Strauss's Elektra, to critical acclaim--an accomplishment of which I am very, very proud.

I thank you, John, for being my angel on Earth during one of the darkest periods of my life, when other teachers and advisors were urging me to sing as a mezzo-soprano, although my heart was aching to sing Tosca and Minnie, Turandot and Leonora, and many other beautiful soprano heroines-all of which I eventually performed under your tutelage. I will always be grateful for your guidance, and most especially for your vocal technique, which allowed me to sing the most sublime music, in my opinion, ever composed: the Immolation Scene from Wagner's Die Götterdämmerung. I miss you still, and know that you are having fun teaching angels how to improve their voices!!

It was Marilyn Zschau above all--Lester's star dramatic soprano--whose brilliant world-wide career provided him entrée into the international world of opera. Ms. Zschau made a practice of inviting Lester, as well as his wife, Willa, to accompany her to La Scala, the Met, Chicago, Sydney, and Los Angeles, when she was singing her demanding repertoire. Through these sojourns to the great opera houses, John Lester was often approached by Marilyn's leading colleagues for vocal help. He thus became known throughout the international opera community as a master vocal technician and teacher.

In the late 1970s, Lester met Philippino-American tenor, Otoniel Gonzaga, a singing colleague of Joanna Lester with the opera in Trier, Germany. An association developed that resulted in his subsequently being invited to live during the winter months over a stretch of years at the Gonzaga home near Frankfurt/Main, where "Tony" was engaged as a leading tenor. With this seasonal home base in Germany, Lester's student contingent of professional singers continued to grow.

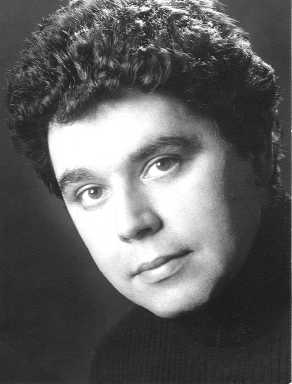

Otoniel Gonzaga, January 10, 2005:

John Lester was more than a voice teacher to me and my family. He was a father to my wife, Christina, and me, and a "real" grandfather to our three children. As a voice teacher, he was a perfectionist. Although I had studied under well-known teachers, John was the only one who was able to strengthen my voice and enable me to move from a healthy lyric tenor singing Mozart and Donizetti, to a dramatic tenor singing Verdi's Manrico and Puccini's Calaf. He made me so aware of technique that I was able to get through the most strenuous roles with the least amount of difficulty. It was John's teaching that enabled me to sing four Otellos in four cities in four days, or nine Florestans in a row, and live to tell about it! I met John in the late '70s, and worked with him until his death. For my family and me, John was the most wonderful person to ever enter our lives. He was a great blessing for us.

Years later, Lester wrote, "Teaching at the University was the most important part of my career and an invaluable preparation for working with singers in Europe, who were facing problems and needed somebody. I had also accumulated enough experience with broken down voices, and this set me forth with a reputation all over the world. I have spent most of my life solving problems of the singing voice. Providing vocal instruction and seeing singers improve over time has given me great personal satisfaction, and has been the central mission of my life."

Reflecting on the role Lester's training played in his opera career, Donald George, first-rank American tenor, who is continuing with a versatile international career in concert and opera, wrote on December 30, 2004:

I was overjoyed when I discovered John Lester! He was a master technician, and was able to convey his knowledge of the voice to me through a vast array of methods and devices. His was a method of taking the voice apart and then putting it back together again. We would work on specific muscle actions and build them into exercises, then into arias and roles I was preparing. His basic idea was to build a vocal and physical memory through various vocalises, allowing you to take ownership of this memory, recalling the particular sound you needed. When John felt the sound and the physical characteristics were correct, he would first have you repeat it, and then do it the old way so that you could understand the difference. Then, we would apply the newly won technique to a particular piece of music.

I'm able to "take apart" my voice when I have a problem in an aria or vocal passage, much the same way John did. I have the ability to think in a dual manner: that is to say, I think musically and also watch to make sure that all elements of the voice are working harmoniously together. I owe all of this ability to John, and thank him for giving me the chance to appear in the fine opera houses where I have sung. He was a master teacher, and it was a privilege to have known him as a wonderful Mensch.

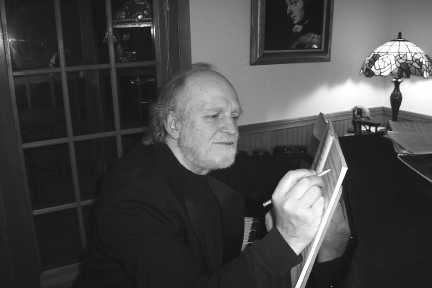

Speaking for a video interview filmed in Seattle, the 90-year-old John Lester summed up his personal philosophy as a deeply thoughtful inspirer of vocal artists:

"Eventually, a fine singer goes beyond all of the mechanics and expresses the qualities that make us human--humor, anger, love--all have to jump forth! The vocal instrument is given to us by our Maker. I don't know just where God is or what God is--but I believe firmly in God. I think that anytime we harmonize our activities in accordance with the organization of anything as God presented it, we get creativity. I think of the voice: We've been given these muscles, and so forth, and they're made to function in a certain manner. God planned that. When we are using the voice as it was intended to be used, we get creativity. Whenever anything is properly managed according to the harmony of the elements that make up the universe and according to the plan that the maker gave us--all these things--we get creativity."

Notes

Gary Funk studied with John Lester from 1966 to 1969. He is currently Director of Choral Activities and Director of the Vienna Experience in the Department of Music at The University of Montana-Missoula. (See his "The Vienna Experience: The Role of the Arts in Liberal Education" in TMP 14.1 [Fall 2003].) In addition to his direct faculty responsibilities Prof. Funk regularly performs as tenor soloist.

Robert Hoyem studied with John Lester from 1949 to 1954. Upon his graduation from UM he earned a Masters Degree in Voice from the Manhattan School of Music, and studied in Germany as a Fulbright Scholar for two years. He remained in Europe, performing and directing opera, and teaching voice until his recent return to Missoula, where he continues to teach privately.[Back]

The University of Montana-Missoula was known as Montana State University 1935-1965; Montana State University-Bozeman was designated Montana State College.--Ed.[Back]

University enrollment was then 1,500-1,800.--Ed.[Back]

[The Montana Professor 15.2, Spring 2005 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]