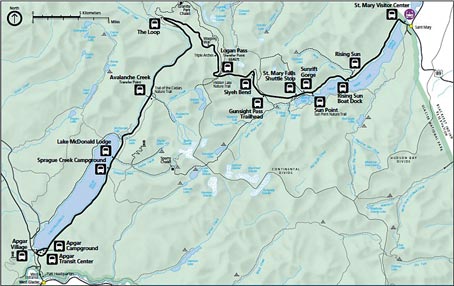

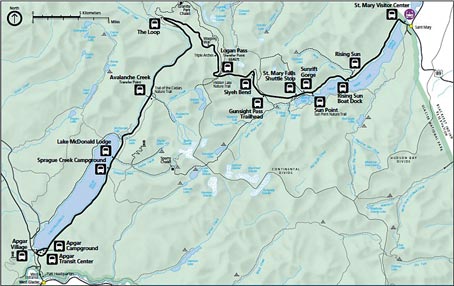

Figure 1. Transit stops on the Going to the Sun Road, Glacier National Park.

[The Montana Professor 23.1, Fall 2012 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Wayne Freimund, PhD

Professor of Protected Area Management and Director, Wilderness Institute

University of Montana-Missoula

I was born in Montana, and so I would come here a lot growing up, and it's one of my favorite places on Earth, I think it's one of the most beautiful places I've been to, so I take people back when I can. —Glacier visitor, 2011

Like this visitor, when you envision Glacier National Park (GNP), you likely see pristine mountains, waterfalls, spectacular wildflowers, clear running streams, and abundant wildlife. Indeed, that is all part of what makes Glacier a defining feature of the Crown of the Continent. Glacier is also an important anchor for Montana's tourism industry and provides hundreds of millions of dollars to our economy each year (Stynes, 2010). It receives nearly two million visits each year, largely compressed into the months of June, July, and August.

The Going to the Sun Road (GTSR) is the primary route through Glacier National Park. In 1932 construction was completed on the road which connects the east and west entrances of the park and is a main attraction for visitors. Over two million people visited the park in 2009, and 80% of those visitors traveled the Going to the Sun Road.

A ten-year construction project to rehabilitate the GTSR began in 2007. To mitigate the effects of the work on park visitors and local businesses, GNP implemented a free shuttle bus system along the GTSR that services the area from Apgar to St. Mary (Figure 1). The shuttle system is just one element of a plan to minimize disruptions to visitors traveling the road during reconstruction and reduce impacts on park values in the long run (NPS, 2003). The congestion problems faced by Glacier are common through the National Park system and there is considerable interest in mass transit as a means to manage social demand for parks. Thus, the success or failure of Glacier's traffic management system has considerable importance for parks on a national level. Will the system work as intended, or will there be larger issues created as a result of it?

Since 2005, the author and numerous UM students have been monitoring the use of The Going to the Sun Road Corridor and surveying visitors about their interests, behavior, likes, and dislikes relative to the transportation system and the park in general. This partnership with the park has been a rich learning experience for all parties involved. To mitigate the impacts of changes in use patterns, we are now working together on a visitor management plan for the corridor.

The research reported here has occurred in four phases over 7 years. In 2005 and 2006, we provided observational data on visitor types and distribution at viewpoints along the GTSR and key parking areas. We made over 8000 observations and interviewed 850 visitors (Freimund et al., 2005, 2006a, 2006b). A stakeholder evaluation was completed in 2007 after the shuttle system's first year of operation. Comments were gathered through visitor surveys, interviews with local constituents and concessionaires, park volunteers, shuttle drivers, traffic management personnel on the GTSR construction team, and park staff. The evaluation provided an assessment of the quality of the shuttle service and recommendations for improvement (Freimund & Baker, 2007). A 2009 survey of drivers, shuttle riders, and hikers was conducted at Logan Pass and the Loop. The data provided information about how the transit system influences visitor use of roadside viewpoints, the relationship between the shuttle service and hiker decisions about taking long day hikes, and how visitors use information about the transit system (Dimond and Freimund, 2009). In 2011 we assessed parking lot use at the Avalanche and Sunrift Gorge parking lots, monitored trail use via visitor-carried GPS at the St. Mary and Hidden Lake Trailheads, and—through the use of infrared trail counters—estimated trail use at eight locations along the corridor with (Bedoya & Freimund, 2012)

The studies revealed that the transit system is highly popular for the visitors that ride it. But it is also changing and sometimes adversely impacting visitor experience and visitor use patterns along the GTSR corridor (Freimund et al., 2006a; Dimond & Freimund, 2009). The demand for the shuttle far exceeds original ridership goals and has increased over the years since implementation. Results also suggest that the shuttle is increasing the number of visitors who take longer hikes on trails, and that the transit system facilitates return trips from geographically separated trailheads (Freimund et al., 2006a; Freimund et al., 2006b).

For example, almost three quarters of the hikers sampled on the Highline Trail in 2009 used the shuttle to facilitate a one-way hike on the trail. However, 70 percent left their car at either Logan Pass or the Loop. Sixty-eight percent of them selected the hike, in part, because the shuttle was available. Therefore, even though hikers were using the shuttle, and it influenced their choice of hike, they were also driving much of the GTSR and leaving their vehicles for most of the day at highly congested parking lots (Dimond & Freimund, 2009). Before the shuttle was implemented, many parking lots were often at or above capacity as they continue to be now. While frustrating for drivers, this limited visitor numbers at roadside viewpoints and trailheads and indirectly limited the use levels on trails in the GTSR corridor. With the addition of the shuttle, both parking availability and limits on trail access are reduced.

Until 2011, trail use of monitoring had not occurred since 1988. The 1988 estimate for Avalanche Lake trail (a popular trial adjoining the road) use was 26,200 visits between May 21st and September 5th. Our 2011 estimate on the same trail was 55,170 visitors during the summer season (July 1st to September 5th) which amounts to an average of 796 people per day. An additional 13,068 visitors hiked Avalanche from September through November of 2011 and while we did not monitor in June, there was substantial use. According to the NPS public use statistics office, in 1988 the park received 1,817,733 visits and in 2011, just 35,831 more for a total of 1,853,564 visits. Thus, it appears that use relative to overall park visitation on the Avalanche Lake trail has increased by as much as 250 percent since last measured 23 years ago. Among the trails monitored during 2011, Hidden Lake presented the highest visitation levels with an average of 811 visitors per day and Highline Trail experienced a summer average of over 620 people per day. The average daily use in St. Mary was 370 visitors (Bedoya & Freimund, 2012). The trails associated with the road are very busy and many visitors will encounter as many as 100 other visitors per hour.

For decades, access to Glacier's backcountry has been limited by parking lot availability. The addition of mass transit to the system reduces that limitation. In addition, it is possible that the availability of the shuttle system is attracting a slightly different visitor, one who is more interested in experiencing the park by foot, rather than by driving. Thus, the transit system is providing new experiences of high quality. Visitors who use the system are generally very pleased with it and have new opportunities for looped hikes. The unintended consequences of the system include no net improvement in parking availability, increased use of some backcountry trails, and less reduction of cars in the park than was anticipated at its onset.

When the reconstruction of the road ends in 2014, efficiencies will be gained in traffic flow and the shuttle will be able to deposit considerably more people into the system than it is currently able to do. The ongoing financial sustainability of the system may also require gaining economies of scale that would encourage adding more shuttles and increasing service quality (less waiting for shuttles to arrive). Together, these possibilities have led park management to begin a planning and research process that will anticipate scenarios of increased visitation demand and how the exceptional Glacier experience can be protected within those scenarios. To support that plan, UM researchers will model the relationships between vehicle traffic levels and use of key trails within the corridor. With those relationships we will project and analyze alternative demand scenarios and management approaches as they relate to visitor experience quality, wildlife interactions, wilderness values, economic impacts and cost for management. The Going to the Sun Road Corridor is special to Montana and to the park visitors. This plan will address increased demand for the park in a foresighted way and ensure it remains accessible yet wild and primitive. From a national perspective, our work at Glacier illustrates how national parks function as systems. You cannot manage a road with having impacts on the pristine nature of the backcountry as well.

References

Baker, M. L., & Freimund, W. (2007). Initial Season of the Going-to-the-Sun Road Shuttle System at Glacier National Park: Visitor Use Study. Missoula, MT: University of Montana Department of Society and Conservation.

Baker, M. L. (2008). An Evaluation of Visitor Decisions Regarding Alternative Transportation in Glacier National Park. Missoula, MT: University of Montana Department of Society and Conservation.

Bedoya, D., & Freimund, W. (2012). Use of Selected Trails and Parking Areas on the Going-To-The-Sun Road: Interim Report. Missoula, MT. University of Montana Department of Society and Conservation.

Dimond, A., & Freimund, W. (2008). Recreational Use of Selected Viewpoints on the Going-to-the-Sun Road, 2008. Missoula, MT: University of Montana Department of Society and Conservation.

Freimund, W., McCool, S. F., & Adams, J. C. (2006a). Recreational Use of Selected Viewpoints on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 2005. Missoula, MT: University of Montana Department of Society and Conservation.

Freimund, W., Baker, M. L., & McCool, S.F. (2006b). Recreational Use of Selected Viewpoints on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 2006. Missoula, MT: University of Montana Department of Society and Conservation.

National Park Service (NPS). (2003). Record of Decision: Rehabilitation of the Going-to-the-Sun Road, Glacier National Park. Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/archive/glac/pdf/gttsr-rod03.pdf.

Stynes D.J. (2011). Economic Benefits to Local Communities from National Park Visitation and Payroll, 2010. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2011/481.

[The Montana Professor 23.1, Fall 2012 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]