[The Montana Professor 24.1, Spring 2014 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Jill Davis, MA

Senior Instructor of Writing

MSU-Bozeman

"I wish you courage to ask of everything you meet: what bridge are we?" —Mark Nepo

Zach, a first year writing student, stood before the group of 30, legs shaking, hands quivering, and after taking in a deep breath, began reading from his essay.

While growing up, I was oblivious to the three suspects that burglarized one of my family's most cherished possessions. Drugs, disability, and disappointment crept into our home while at the same time casting my sister to the streets. In hindsight it is clear my sister Hayley was homeless while still living under the same roof as the rest of us.... I have to admit, with a degree of guilt, that it was almost comforting during those periods my sister was amiss. Her absence meant less stress in the house. No confrontations about her choices, directions, and friends. I know for certain that part of her reason for running was to give us relief, to save us from the effect she had on the family. It was a battle, never to be won. We were trying to save her, she was trying to spare us, and no amount of family fighting, church influence or family counseling was going to keep that train wreck from happening. The silence we now experience from her absence is louder and more disruptive than any of her worst outbursts....

Zach continued his poignant interview essay bridging his sister Hayley's story to "Loretta's"—about a homeless mother of two—whom he met at The Bozeman Homeless Connect Day. He closed with these words.

I wish for all of you, a personal connection with one of the nearly one million Hayley's and "Loretta's" that are on the streets today, and hope you find that the condition of homelessness is shared by us all. I see my sister's face in every homeless individual I meet. And no matter whom it is that wears Hayley's face, as long as they are experiencing life without a home, there will be a part of me that is homeless as well.

The project Zach signed up for in our WRIT 101 course was the Homeless Connect Yearbook Project, which interviews housing-challenged individuals and offers them a platform to tell their stories of adversity and triumph. Like many other students, Zach attended Homeless Connect, a day Bozemanites come together to offer struggling individuals one-stop access to a broad range of services in a welcoming environment. Six weeks later on a snowy day in February, he, along with some of his classmates, read his essay to the members of the Greater Gallatin Homeless Action Coalition, the mayor of Bozeman, and other key stakeholders in the community. Zach and his fellow students wrote draft after draft, revising frequently; each student needed to get it just right. Their essays not only had to honor the individuals who shared heroic stories about living under immense challenges but also to educate and advocate in a meaningful way.

That day in February when Zach finished reading his essay, he noticed tears in the eyes of some of his listeners. He realized then that he had accomplished his mission of using his writing to stimulate organizers into compassionate action:

I never thought that I could touch people with my writing. I have, and now I know what that feels like. It is amazing!"

"Stories heal," Maya Angelou is noted for saying, and my students have learned the truth of these words through our interview initiatives. Stories kept the ancients around the first campfires and inspired them to paint epics on cave walls. Stories entertain, stimulate, educate, and give both teller and listener a sense of connection. Stories are known to open doors to new perceptions. This is why I use stories to bring about "social action."

Helping my writing students find meaning in their composition work and their academic careers is a passion of mine. My intention is to ignite a similar passion and interest in writing and help them find audiences who need to hear their words. When I discovered Thomas Deans's work on cultivating writing practices for, about, and with community in his Writing Partnerships: Service Learning in Composition, I knew I had hit paydirt. Deans provides a two-fold scholarship process that addresses community needs together with structured educational objectives intentionally designed to promote student learning and development. Many college campuses across the United States have taken greater pains to involve students in a distinctive form of active learning that combines academic skill development with service projects. This movement has its roots in the action-reflection theories of John Dewey, who understood the importance of connecting theory, action, and reflection to bring about greater learning competences. In most academic circles today, with the help of scholars like Christy Price, 2012's Carnegie Foundation's Professor of the Year, instructors corroborate curriculums built on innovative teaching methods that stimulate scholarly performance, increase student understanding of the responsibilities of living in a democratic society, and encourage student involvement in the social problems facing their communities (Crews 1999). Price (2009:5) defines optimum learning as those conditions that employ research-based methodologies built on clear rationales, relevant information, and purpose-driven pedagogies, thus furthering Dewey's notion that "knowing emerges from palpable experience, and is realized in action" (Deans, 2000, p.32).

In order for students to experience writing as a "social action," I have found it advantageous to "move the writing instruction out of the classroom into the community" (Heilker 1997:71). The outcome of such practice generates an evolution from transactional composition methodology to a transcendent writing practice with engagement providing the scaffolding for the pedagogical "lift." Robert Nash, author of Helping College Students Find Purpose (2010), puts it this way:

The search for meaning is most likely to be successful on college campuses where students see the deep connection between subject matter, marketable skills, their personal values, and their interests in contributing to the common good- whether by performing community service to others, or dedicating themselves to a social cause that results in self-transcendence. (p. 87)

A Community-Engaged Scholarship Model

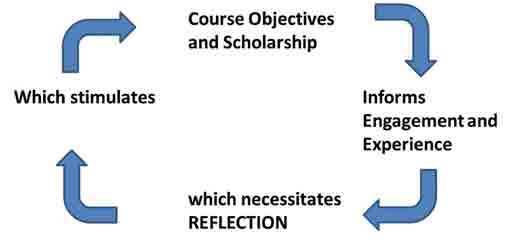

When skills and a sound knowledge base are attained in first year composition classes, they can be further enhanced with engagement experiences and a rigorous reflective process which expands and deepens scholarship acumen. The reflective process is integral since it "transforms experience into learning" (Hutchings & Wutzdorf, 1988, p. 15).

In 2009, when Family Promise of Gallatin County invited my students to utilize writing and interviewing skills to produce the Homeless Connect Yearbook, a project that had been piloted in both Seattle and Portland, I realized this opportunity was a perfect experiential match for our theoretical course readings, research, and discussions. When I pitched the idea to my students, they jumped at the opportunity for two main reasons: 1) they wanted to learn first-hand the challenges homeless individuals faced, and 2) they wanted to collaborate with community members to advocate for constructive services and positive change.

After participating in interview training sessions and a research process concerning national and local housing challenges, my students attended the first Bozeman Homeless Connect Day. With waivers, recording devices, and gas vouchers in hand, students found a plethora of individuals willing to be interviewed.

After completing the interviews, students transcribed conversations and wrote narratives which included thoughtful reflection discussing misnomers, stereotypes, and confusions they held about displaced and marginalized individuals. One student commented,

Growing up in Montana, I've lived a pretty sheltered life and never spent time listening to a homeless person's story. But while interviewing at the Homeless Connect Day, I learned how I've been stereotyping homeless people in diminutive ways and that is not OK anymore."

Word got around the community that these student-writers had something important to say, so they were invited to present their findings to organizations including Rotary, local church groups, various senior centers, and Family Promise. Students read essays and presented their projects to the ASMSU Senate, and the Bozeman Daily Chronicle digitized and archived the student stories for public record. Additionally, their stories were published for the National Coalition for the Homeless.

In 2009, we expanded our work to include two other projects. The FACES Project, which consisted of student interviews with Sexual Assault survivors on the MSU campus with the mission to educate fellow students and advocate for services with the VOICE Center. As one interviewer reflected,

Our class wanted to educate our student body and eradicate this problem forever. When we read our essays at Take Back the Night, I couldn't believe how many people came up to us and thanked us. It felt really good to know I was actually doing something in a writing class to hopefully make our campus safer."

Another project was The Resiliency Project: Interviews with Remarkable MSU Students, consisting of interviews with fellow students who had triumphed over adversity. One undergraduate gives testimony to the power of this project:

I didn't know that the person sitting next to me in Physics was getting chemo treatments every Friday morning—that is not until I participated in interviewing for the Resiliency Project for my writing class. I was so inspired by her story and that she went to all of her classes while doing chemo. She is my new found hero!"

All of these projects were published in one form or another, and students presented their work at local venues. One engineering student commented,

I think it's really awesome that this writing class encourages us to get into the community and interview people who have been through hard times and use our interviews to make their lives better and ours too." Students have a choice of projects and then are partnered with suitable interviewees. While presenting these various projects to seniors at an assisted living facility, an individual asked, "Why not interview us?" Thus began the Tuesdays with Morrie Interview Project modeled after Mitch Albom's narrative about his weekly visits with Morrie Schwartz.

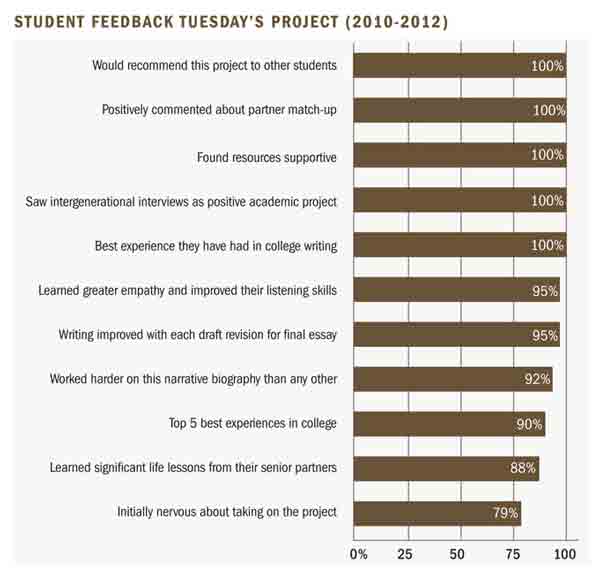

Unlike our other projects which consisted of one-hour interviews culminating in a biographical narrative/reflective essay, the "Tuesdays" project requires a ten-week meeting commitment with a senior elder to learn about his/her life story. Because we live our lives forward and understand them backwards, reminiscence is common at the end of life, and our seniors find it helpful to reflect with an attentive, thoughtful listener, while students find it beneficial to slow down and share the fabric of their busy lives with an elder who cares and offers sage counsel. The descriptive narratives produced by students are seen as valuable documents for the interviewee's family, as was recently realized when a portion of a student essay was read at his partner's memorial service. It has been heartwarming to witness the bonds that form from these partnerships and the challenges emerging from inevitable differences. What began as an oral history interview endeavor has progressed into meaningful intergenerational dialogues with enlightened discussions and inspirational outcomes. Heather, a health and human development student, wrote,

After spending eight weeks with Stu..., I realize his life changed many, including mine. I entered this project hoping to write a paper to honor someone's life. I hope I have accomplished that, but now it is something so much greater. I know now that Stuart Knapp entered my life to inspire me. To show me that nothing can hold me back from my dreams. To show me just how much one person has the potential to positively influence the lives of many others."

In addition, the Reflection Practice:

Student journal entries radiate with exuberance for the project. A second year cell biology student said:

What I learned from AJ will change the future of my work as his introduction and stimulating example of volunteerism.... I also could see my writing improve tremendously in the weekly help sessions...working with brainstorming, concept mapping, outlining, and small group draft work, all of these were very effective in helping me write the best essay possible. I completed six drafts before getting to the final version, which is rare since I have revision-aversion. ...Never have I seen a class come together and become friends in an academic setting like we did. It was entirely due to...the classroom environment, and how excited we were about the project.

Sharon Daloz Parks reminds us that students continually ask faculty, "What is the purpose of our curriculum and how does it apply to real world needs?" They want to know how one curriculum is connected to other curriculums; they are searching for a sense of connection, pattern, order, and significance. These interview projects address Parks's concerns and provide strong connections between course content, outcomes, philosophy, and reflection by offering civic learning experiences that bring about meaningful and purposeful scholarship for students.

When a first-year writing student like Zach stands before a formidable audience to share an essay containing his thoughts and feelings about his interview experience, and when he moves his audience to tears with his words, I know I am experiencing something extraordinary. What greater gift can a teacher receive than watching her students build stronger bridges of self-efficacy through civic engagement?

The process for Tuesdays with Morrie Interview project.

References

Crews, R. (1999). Benefits of service-learning. Communications for a sustainable future. Boulder, CO : University of Colorado at Boulder.

Deans, T. (2000). Writing partnerships: service learning in composition. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English Press.

Heilker, P. (1997). Rhetoric made real: Civic discourse and writing beyond the curriculum. In L. Adler-Kassar, R. Crooks, & A. Watters (Eds.). Writing the community (1997 ed.). Washington DC: American Association for Higher Education.

Hutchings, P., & Wutzdorff, A. (1988). Experiential learning across the curriculum: Assumptions and principles. In P. Hutchings & A. Wutzdorf (Eds.). Knowing and doing: Learning through experience. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Nash, R. & Murray, M. (2010). Helping college students find purpose. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Parks, S.D. (2000). Big questions, worthy dreams. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Price, C. (2009). Why don't my students think I'm groovy? The Teaching Professor, 23 (1).

[The Montana Professor 24.1, Spring 2014 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]