[The Montana Professor 24.1, Spring 2014 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Keith Edgerton, PhD

Associate Professor of History

MSU-Billings

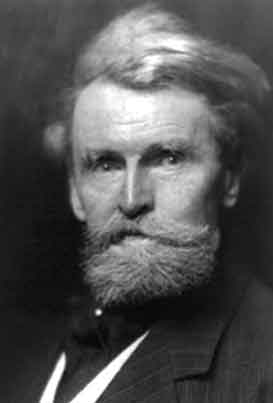

William Andrews Clark was among the most powerful, influential, and ruthless of the 19th century American robber barons. Today, however, he is virtually anonymous. In fact, he may be the most famous—or infamous—person no one has ever heard of, especially outside of his adopted state of Montana where he was one of the vaunted copper kings who developed Butte into a world-class mining center. More surprisingly, no one has written a full-length biography of him. There have been any number of historical studies written around the peripheries, focusing primarily on the Butte he helped build and finance, but there has been no sustained attempt at chronicling his vast, complicated, and sprawling eighty-six-year life. A few years ago after a night in his Butte mansion he built in the 1880s (since converted to a bed and breakfast), my significant other suggested I take on the project. With any expansive endeavor, particularly researching and writing the biography of one of America's super-rich, one never really knows what one is getting into. Four years into the project (and counting), there have been a good many peaks and valleys with undoubtedly many more to come.

Clark lived in an age (1839-1925) when his more well-known peers included John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and Andrew Carnegie, all household names and each a captain of American industry at the time. Certainly Clark was one of the wealthiest, if not personally the wealthiest, man in the country during a time when the true measure of an individual's social and evolutionary fitness was the unapologetic, relentless, and successful accumulation of vast sums of capital. By that standard Clark was arguably the fittest of them all. And in Montana history, no one's shadow looms larger. Starting with nothing in the early 1860s, then making a fortune first in banking in Deer Lodge and then in western copper mining—foremost in Butte where he bought up played out silver mines and then turned them into industrial-strength copper producers—for roughly the two decades framing the turn of the nineteenth century, Clark went toe-to-toe in national notoriety with his more illustrious counterparts. In the process he became a lightning rod for sustained public wrath, vicious enmity, even hatred. After a brandy-soaked dinner in 1907, Mark Twain described him as "as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag;" and "a shame to the American nation."/1/ Throughout his adult life, however, Clark's self-taxing work habits and his unmitigated talent for stockpiling unparalleled wealth were sources of endless fascination for an American public who historically have been drawn to the lives of the filthy rich.

And make and spend lots of money Clark did. Upon his death in 1925 observers conservatively calculated his fortune at over $200 million. In contemporary terms, that would be roughly equivalent to $31 billion; only Bill Gates and Warren Buffett exceed that total. Among his contemporaries only Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Morgan amassed more, though in their later years they began ambitious and far-sighted philanthropic projects, divesting themselves of vast portions of their riches or splitting their wealth among various corporate spin-offs. Clark never did. For over a half century, as he built a financial empire that stretched across the nation and employed thousands; every business venture William Andrews Clark touched turned to gold. Along with an elite handful of like-minded capitalists, Clark helped create what became, as the writer Charles Morris has called it, the American "supereconomy" that fueled the sustained boom of the 20th century. After Clark reached the Senate in 1901, fellow senator Robert Lafollette astutely identified him as one of the 100 men who owned America. His story reveals naked and shameless ambition—and raw unrestrained greed at its basest level. Clark's life is a primer on the limitless power money could buy and reveals, in unvarnished terms, just how far one might go in the free-wheeling world of early 20th century American-style capitalism. Clark surely would have heartily endorsed Gordon Gecko's famous creed in Oliver Stone's film Wall Street: "Greed is good."

Yet in spite of his notoriety, or perhaps because of it, the public adulation he desperately craved eluded him, and pundits like Twain and a sensationalist yellow press savaged him mercilessly for the nearly twenty years he remained in the public eye. Many viewed him as a shameless parvenu who purchased his way into the Senate and then elbowed his way into the upper crust New York world of Big Money and high society. From 1888 until 1900, he failed in four separate, bitterly contested campaigns to win a US Senate seat from Montana, incurring both the enmity and the weird fascination of an American public who followed his many controversies and peccadilloes.

Similar to his celebrated corporate counterparts, Clark was born in the late 1830s, and like those other financial leviathans, he began with a life of modest means. His story, like theirs, was—and still is—a classic Horatio Alger tale. After a brief stint as a rural school teacher and an even briefer stint soldiering in Civil War Missouri (it's unclear on which side he served), he arrived in the gold fields of the American West in the early 1860s with only a pack on his back and the ragged clothes he wore. His truly is a rags-to-riches saga. Like Rockefeller, Gould, Carnegie, and Morgan, ultimately Clark would amass a titanic-sized fortune, complete with a priceless European art collection and the most expensive monstrosity of a 5th Avenue Gilded-Age mansion the bluebloods of New York City high society had ever seen. Still today architectural historians consider the mansion (sited directly across from Central Park, though demolished in 1927), as the most expensive private home ever constructed in New York City.

Clark's long list of accomplishments, while inseparable from his political chicanery in his adopted state of Montana, are many. His brazen purchase of nearly the entire 1899 Montana legislature which resulted in his long-sought election as U.S. senator, contributed substantially to a Progressive-era populist groundswell that contributed to the passage of the 17th amendment to the Constitution in 1914, allowing for direct election of United States senators. Before that, he was the president of the 1889 Montana constitutional convention, and his mineowner-friendly fingerprints were all over that document./2/ As such, he was instrumental in laying much of the legal foundation for later 20th century corporate and political abuses by the Anaconda Company. With his deep-pockets—and after a bitterly contested state race financed by his chief Montana rival, fellow copper king, Marcus Daly—Clark ensured, mostly singlehandedly, that the state capital of Montana became Helena; still today, its capitol dome bears a copper patina from his mines. Farther afield, Nevadans consider him the founding father of a then-obscure and dusty little railroad watering stop in the southern part of the state that Clark and his brother bought and then began developing to assist their southwestern railroading empire. Las Vegas is the county seat today, fittingly, of Clark County, Nevada.

Clark was variously a farmer, a teacher, a soldier, a prospector, a wood-cutter, a teamster, a cattle driver, a grocer, a mining engineer, a banker, a real estate tycoon, a railroad magnate, and the developer of the southern California sugar beet industry. He claimed success in every endeavor. While in his 70s he became fluent in both French and German in order to consume, voraciously, as much literature about art collecting that he could manage to squeeze in during his routinely jam-packed, twenty-hour work days. During the forty-year period he called Montana home (the 1860s to the early 1900s) he lived at times in a covered wagon, a tent, a sod dug-out, a log cabin—then as a boarder, in a rented frame house, and ultimately in a Butte mansion whose walls he purportedly had adorned with pulverized gold dust mixed with the paint and illuminated with natural light streaming through imported Tiffany stained glass. Though barely five feet six inches tall, he led a life as big and as expansive as the country itself was becoming, fueled by his keen intelligence, a relentless stamina, obsessive attention to detail, and taking advantage at every opportunity of a predominately laissez faire economic regulatory environment. Clark was both a robber and a baron in the truest sense of those terms and he possessed, as one Montana historian noted, "a plunger's genius for comprehending the rewards to be had in gambling on a large scale."/3/

His private life was no less sprawling or complicated than his public one. Clark fathered at least nine children with two different women. His mysterious and beautiful second wife Anna was a product of the rough-and-tumble Butte boarding house world, thirty-nine years his junior and who would outlive him by another thirty-eight (she died in 1963). His last child, a daughter, Huguette, was born in 1906 when he was sixty-seven. Remarkably, she lived until 2011 in New York City as a pathological recluse who had not been photographed in public since 1930 and who owned mansions she never occupied on both coasts and one of the toniest 5th Avenue apartments in New York, maintained but vacant for the last twenty-two years of her life. A hoarder, Huguette was the sole heir of the remnants of her father's vast fortune; her estate is currently the focus of a protracted legal battle between her former caregivers, attorney, and accountant and distant relatives by Clark's first marriage. Sixty boxes of historical material are currently in dispute, putting my own historical research in limbo. Two books on Huguette's odd life alone by two different New York journalists are in the final stages of publication./4/

Despite concerted efforts, bordering at times on the obsessive, to establish a lasting historical legacy, Clark himself has been largely forgotten./5/ His anonymity can be partly explained by the fact that he accumulated his enormous fortune and made his mark in some of the most remote reaches of the late nineteenth century American West. Outside of the perennial interest in the dénouement of George Armstrong Custer (his 1876 "Last Stand" occurred on the eastern Montana Plains), or on the other, though more celebrated, William A. Clark, part of the exploring tandem of Lewis and Clark in the early 19th century, Montana history, after all, is not front and center in the nation's history. Individuals like Clark, no matter how disreputable or deliciously execrable, have languished on the historical back burner. Unlike his more renowned contemporaries, and despite his vast fortune, Clark left no large or lasting national philanthropic monuments; there are no universities, endowed chairs of research, or libraries bearing his name or thriving because of his money./6/ During his lifetime Clark controlled his financial kingdom exclusively. There never existed a "William Andrews Clark Corporation" and accompanying corporate empire. Everything was his, and his alone. Upon his death in 1925 his immediate family heirs donated only an eclectic collection of primarily 19th century French art work to the private Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, D.C. (and this after the Metropolitan Art Museum in New York turned it down). Most of it today remains in storage hidden from the public. Montana, the wellspring of his vast fortune, certainly got the short end.

Clark also made much of his money in, and obtained most of his clout through, one of the least glamorous industries—mining—and extracting, on an industrial scale, one of the least glamorous of metals—copper. Copper has never been as seductive and as alluring as gold or silver. It just isn't a very sexy metal. For generations pulp and popular writers of the American West have treated readers to colorful tales of the 49ers and the gold rush to California or the silver strikes of the Comstock Lode in the Sierra Nevada (and more recently the gold-strikes of the Dakotas in HBO's series "Deadwood"). The gritty Western inner-mountain world of industrial-strength copper mining complete with its sulphorous and arsenic fume-belching smelters and its determined, hard-rock, unionized, and mostly immigrant laborers—the world and people which propelled Clark to national prominence and, ultimately, infamy—are not the stuff of romance or classic Hollywood westerns. Nonetheless, it was copper from his mines that helped electrify America precisely at the moment when Edison's Menlo Park light bulbs most needed it. It was copper from his Montana, and later Arizona, mines which conducted the electricity that in large measure fueled the meteoric late nineteenth century industrial expansion in the United States, thus positioning it as a looming world power on the precipice of the twentieth century.

Notes

[The Montana Professor 24.1, Spring 2014 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]