[The Montana Professor 25.2, Spring 2015 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]

Blakely Brown

Professor, Department of Health and Human Performance

University of Montana Missoula

Obesity/overweight has been declared an epidemic and a "public health crisis" among children worldwide.1 The prevalence of pediatric overweight in the U.S. tripled between 1980 and 2000. African Americans, Latinos and American Indian (AI) populations have the highest prevalence of obesity among North American youth.2 Overweight in children is defined using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) age- and sex-specific nomograms for body mass index (BMI).3 A BMI-for-age between the 85th to the 95th percentile is considered overweight; and ≥95th percentile is defined as obese. Pediatric overweight/obesity has been linked to increased risk for prediabetes,4 metabolic syndrome5,6 and type 2 diabetes,7 with insulin resistance being a primary mediator of these conditions.8 Impaired insulin secretion is also a main feature of type 2 diabetes. Having a first-degree relative with diabetes and being American Indian are risk factors for type-2 diabetes.9 Studies show that minority children are more insulin resistant than non-minority children, regardless of degree of adiposity and other biological and behavioral factors.8 Although Montana ranks low in the nation (46th) for overall prevalence of childhood overweight/obesity,10 our surveillance study of five rural Montana Indian reservations found approximately 57% of AI youth ages 5-19 years old were overweight/obese.11

Evidence from prior studies9-14 suggests behavioral approaches that increase daily physical activity and decrease caloric intake can reduce risk factors associated with childhood overweight and obesity. However, the prevalence of childhood obesity has tripled in the last three decades,12 suggesting additional strategies are needed. Individual behaviors that contribute to obesity, such as diet and exercise, are influenced by factors such as early childhood development, income, education, food security, and chronic stress that impact health in general and work synergistically on individual, community, and societal levels.13,14

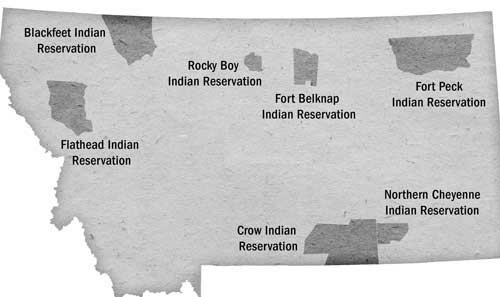

There is great diversity among the twelve tribal nations of Montana in their languages, cultures, histories, and governments. Each nation has a distinct and unique cultural heritage that contributes to modern Montana. Each of the seven Indian reservations in the state has its own tribally controlled community college. Under the American legal system, Indian tribes have sovereign powers, separate and independent from the federal and state governments. Sovereignty ensures self-government, cultural preservation, and a people's control of their future.

Developing effective obesity interventions for AI youth that encompass their distinct and unique cultural heritage requires collaborative design of methods based on input from members of the communities in which the interventions are to be implemented. A community based participatory research (CBPR) approach can help identify and support protective factors within Indian tribes and may be the most effective and culturally appropriate way to develop intervention strategies to reduce obesity. CBPR is especially appropriate for use with American Indians who have historically been vulnerable to researchers' insensitivity and exploitation.15 CBPR actively engages community members in the project development and implementation process,16 builds upon existing community strengths,17 and holds significant promise for implementing effective and sustainable public health approaches.18,19 By promoting long-term, equitable partnerships between researchers and communities, CBPR approaches create a balance between the scientific rigors of tightly controlled researcher-driven studies with community control and respect for local wisdom.

Since 2004, the author, several MUS and tribal college faculty and students, and community members from Montana Indian reservations, have been developing collaborative, participatory approaches to preventing obesity and type-2 diabetes in Native youth and adults. The partnership with tribal communities across the state that has occurred over 12 years has been a rich learning experience for everyone involved.

Our seminal preliminary childhood obesity prevention research was conducted in collaboration with two small reservation communities located in rural north central and south eastern Montana. Between 2004-2007 we partnered with tribal health and health board administrators and staff, and community members, to develop and submit a National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases CBPR proposal to adapt an evidence- based curriculum for preventing diabetes in adults to be age and culturally relevant for Native youth, aged 10-14 years. During these years, we also developed a Code of Research Ethics Memorandum of Understanding to guide and set specific protocols for conducting research with tribal communities in Montana. The MOU, approved by UM Legal Counsel, and Tribal Councils at each reservation site, contains protocols for data sharing and ownership, individual and community anonymity, publication and dissemination processes. We continue to adapt the MOU for other studies with Montana tribal communities and UM.

We received funding for the study, and from 2007 to 2010 developed and tested the Journey to Native Youth program (R34DK7446) which was a 9-session, 12 week age and culturally relevant, nutrition, physical activity and healthy weight behavioral program.20,21 Sixty-four Native youth from the two reservation communities were randomized to the Journey program or a health-oriented comparison condition. Parents participated in the first and last sessions and received weekly information sheets. The Journey group significantly increased their overall nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs score by 8% while those in the comparison group had no change. The comparison group had detrimental changes in daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and an increase in sedentary activity while those in the Journey group were protected from these detrimental changes over time. These physical activity measures translated to a 31% reduction in kcals expended for the comparison group and a non-significant reduction of 13% among the Journey group. As expected, given the short (3 month) duration of treatment, there was no overall effect on BMI at end of the intervention. Among youth who were overweight/obese at baseline, however, the Journey program was favorable for reducing BMI growth.21 While the pilot study was helpful for developing study protocols, feasibility, and instrumentation, and its outcomes were promising, the findings suggested that the Journey intervention lacked intensity (i.e., frequency and duration) necessary to result in sustained change in the primary outcome for obesity (BMI category). Further, it did not specifically target family members' support for their child's diet and activity change, and it was specific for Native Americans residing in two linguistically and culturally distinct reservation communities. Since completing the Journey study in 2010, we have received funding to conduct additional studies to address these limitations, strengthen our approach, and augment the work with gardening programs and capacity building projects in reservation communities. These studies are described briefly below.

In 2012, we partnered with the Missoula Boys and Girls Club to conduct a one-year study that further developed family-based materials and tested the feasibility of a high-intensity nutrition and exercise intervention for children attending the Club program. Family members took part in a focus group and interviews, which generated relevant statements for ways to better connect caregivers to what their children are doing in the afterschool program and ways to have children teach caregivers at home. We then conducted a two-week pilot study of the intervention. Seventeen children and 11 of their caregivers participated in a three-day per week, after-school nutrition and exercise intervention that included family activities. 41percent of children enrolled were overweight or obese. Eighty-two percent of the children participated in at least three days/week of intervention activities. Eight of the eleven families participated in family night and five of eleven families attended a nutrition education session. Parents gave high satisfaction ratings to the program. Following the two-week intervention, significant improvements were observed in child outcomes, including knowledge about fat, intentions to eat healthy food, and daily vigorous activity and energy expenditure. Positive parent outcomes included increased levels of parent support for their children's exercise and healthy food choices. Similar to our Journey study, as expected, due to the short duration of the pilot study, no significant changes were detected in children's BMI. However, our findings confirmed this intervention that involves families is feasible to implement and has potential to decrease risk for childhood obesity in an afterschool setting.

In 2013 we received National Institutes of Health funding to further develop the after-school and home-based intervention for Native and non-Native children and families living on a Montana Indian reservation. The Generations Health Project (P20GM103474) is a 2-year collaborative study with the Community Health and Development program at Salish-Kootenai College, the School of Public and Community Health Sciences and the HHP Community Health and Prevention Sciences option at UM, and the Flathead Boys and Girls Club. Similar to the Journey and the Missoula Club studies, we conducted focus groups and interviews with parents of children enrolled in the Club to explore ways to engage caregivers and families in the after school nutrition and exercise program and develop culturally relevant activities for the intervention. Then, the parents' suggestions helped to further adapt the intervention materials. We recently conducted an individually randomized pilot test of the intervention versus a measurement-only condition at the Flathead Club. Twenty-three child/parent dyads participated in the pilot study, 96% were retained in the intervention activities, and 100% completed post-test measures. Preliminary outcomes are encouraging—from pre- to post-test, only children in the intervention group significantly increased minutes of physical activity (as measured by activity monitors) and reported increased intention to eat healthy foods. We are in the process of further refining and expanding the intervention materials, and preparing for a 6-month test of the program on the Flathead reservation, Fall 2015. SCK Students in Allied Health degree programs will assist with the study and gain skills in research and evaluation.

Communities at Play (R13HD080904-01) is a 3-year study (2014-2017) that develops partnerships between Flathead Reservation communities and UM faculty in the Psychology Department, School of Public and Community Health Sciences, and the HHP Community Health and Prevention Sciences option to identify interventions for decreasing the risk of childhood obesity. The setting for this project is the Flathead Indian Reservation located in rural northwest Montana, where the minority of the reservation population is American Indian (24%) and the majority of the population is white. The service systems on the reservation are complex and serve many residents. The reservation is large and—in many places—difficult to traverse. Despite the demographic, socio-economic, and place-based complexities that exist on the reservation, residents and community organizations are interested in working together to overcome rural health disparities and, specifically, prevent childhood obesity. During the first year of the grant, we have established an Advisory Board comprised of 12 community members, and have assessed community readiness to tackle childhood obesity in one of eight communities on the reservation that we are/will be working with. We've also assisted this first community with developing networks with organizations and people interested in organizing further for childhood obesity prevention.

The Gardening Program for American Indians (SP20MD002317-03) was a 2-year, CBPR-based study developed with the Rocky Boys Indian reservation, the HHP Community Health and Prevention Sciences option, and the UM Center for Health Sciences. The primary aim of the study determined the effect of a community garden program for American Indian adults with pre-diabetes and diabetes on glycemic control and mental health indicators. 32 adult participants enrolled in Tribal Diabetes Prevention or Health Promotion programs were recruited, consented, and then randomized into the treatment intervention group (e.g., gardening group) or measurement only group. Of these, 17 participants dropped out of the study for various reasons. At the end of the garden season (end-of-treatment; Fall 2011) there were 7 participants in the garden program and 8 participants in the measurement only group. Participants in the garden program met bi-monthly during the summer months with tribally enrolled project directors, staff and a Master Gardener to take part in 10 educational sessions about gardening. Participants helped construct eight raised garden beds behind the Diabetes Clinic and then grew vegetables and fruits in the community garden area during the summer. Two canning classes were held at the end of the season. Results showed no difference in BMI, blood pressure, or HgbA1C (a marker of glycemic control) between treatment and measurement-only groups at the end of the study. Although there were no differences in depression or quality of life scores between groups, the garden program (treatment) group had significantly better mood scores than the measurement only group. That both groups moved to higher stages of change levels for growing produce at the end of the study suggests the gardening program may have sparked community interest in growing more fruits and vegetables on the reservation. Another positive, sustainable outcome of the study was establishing 36 raised garden beds behind Stone Child College for all community members to use. Rocky Boys also used the data in a USDA and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grants that increased local food production and improved safe routes to schools walking and biking paths.

Over the years, much time and effort has been expended in developing collaborative partnerships with Montana Indian reservations to confront and tackle the obesity and diabetes epidemics in their communities. Understanding the multitude of factors that impact risk for these diseases, and working alongside community members to develop and implement interventions requires a long-term, authentic commitment to create sustainable disease prevention programs. My approach adheres to the Elements of an Indigenous Research Paradigm described in Shawn Wilson's book, Research is Ceremony.22 That paradigm puts forth that the shared aspect of Indigenous ontology and epistemology is relationality and the shared aspect of Indigenous axiology and methodology is accountability to relationships. The shared aspects of relationality and relational accountability can be put into practice through choice of research topic, methods of data collection, form of analysis, and presentation. It is my hope that my ongoing journey of learning in this area with Indigenous scholars, researchers, and community members will enhance our collaborative projects that seek to identify and support protective factors for health promotion and disease prevention in tribal nations.

References

[The Montana Professor 25.2, Spring 2015 <http://mtprof.msun.edu>]